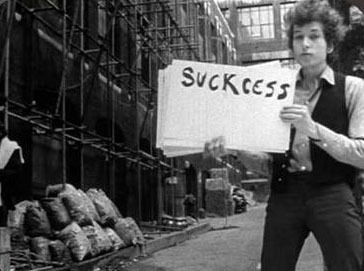

‘Don’t Look Back’ shows a young Dylan: confident if not arrogant, confrontational and contrary, but also charismatic and charming.

17 May 2018 | Various Sources | Hawkins Bay Dispatch – This Day

This Day – 17 May 1967

“… You know the audience that subscribe to TIME Magazine, the audience of people that want to know what’s happening in the world week by week, the people that work during the day and can read it, its small, alright and it’s concise and there’s pictures in it, you know? It’s a certain class of people, its a class of people that take the magazine seriously, I mean sure I can read it, you know, I read it , I get it on the airplanes but I don’t take it seriously. If I want to find out anything, I’m not gunna read TIME magazine, I’m not gunna read Newsweek, I’m not gunna read any of these magazines, I mean cause they just got to much to lose by printing the truth. You know that.” Bob Dylan, 1967

Dont Look Back is a 1967 American documentary film by D. A. Pennebaker that covers Bob Dylan‘s 1965 concert tour in England.

In 1998 the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.” In a 2014 Sight & Sound poll, film critics voted Dont Look Back the joint ninth best documentary film of all time.

The film features Joan Baez, Donovan and Alan Price (who had just left the Animals), Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman and his road manager Bob Neuwirth. Marianne Faithfull, John Mayall, Ginger Baker, and Allen Ginsberg may also be glimpsed in the background.

The film shows a young Dylan: confident if not arrogant, confrontational and contrary, but also charismatic and charming.

21 March 1968 |Don’t Look Back | Roger Ebert

“Don’t Look Back” is a fascinating exercise in self-revelation carried out by Bob Dylan and friends. The portrait that emerges is not a pretty one.

Indeed, those who consider Dylan a lone, ethical figure standing up against the phonies will discover, after seeing this film, that they have lost their hero.

Dylan reveals himself, alas, to have clay feet like all the rest of us. He is immature, petty, vindictive, lacking a sense of humor, overly impressed with his own importance and not very bright.

Australia and Europe Tour – April and May 1966

Dylan toured Australia and Europe in April and May 1966. Each show was split in two. Dylan performed solo during the first half, accompanying himself on acoustic guitar and harmonica.

In the second, backed by the Hawks, he played electrically amplified music. This contrast provoked many fans, who jeered and slow handclapped.[114] The tour culminated in a raucous confrontation between Dylan and his audience at the Manchester Free Trade Hall in England on May 17, 1966.

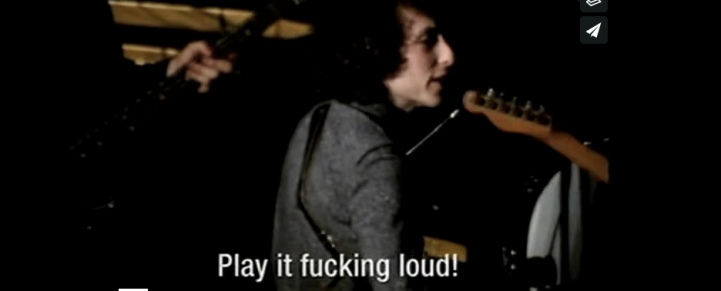

A recording of this concert was released in 1998: The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966. At the climax of the evening, a member of the audience, angered by Dylan’s electric backing, shouted: “Judas!” to which Dylan responded, “I don’t believe you … You’re a liar!” Dylan turned to his band and said, “Play it fucking loud!” as they launched into the final song of the night—”Like a Rolling Stone”.

During his 1966 tour, Dylan was described as exhausted and acting “as if on a death trip”. D. A. Pennebaker, the film maker accompanying the tour, described Dylan as “taking a lot of amphetamine and who-knows-what-else.”

In a 1969 interview with Jann Wenner, Dylan said, “I was on the road for almost five years. It wore me down. I was on drugs, a lot of things … just to keep going, you know?”

In 2011, BBC Radio 4 reported that, in an interview that Robert Shelton taped in 1966, Dylan said he had kicked heroin in New York City: “I got very, very strung out for a while … I had about a $25-a-day habit and I kicked it.”

Some journalists questioned the validity of this confession, pointing out that Dylan had “been telling journalists wild lies about his past since the earliest days of his career.”

Bob Dylan: How I found the man who shouted ‘Judas’

22 September 2005 | Andy Kershaw | Independent

The 1966 bootleg was not only of first-rate sound quality; it was also the most dramatic, confrontational concert I’d ever heard – and I was a regular at Clash gigs at the time.

It remains, for me, the most exciting live album of all. Dylan, on that tour, split his audiences straight down the middle. Many were thrilled by his new psychedelic songs and the massive onslaught of The Hawks roaring through the biggest PA system that had, at that point, been assembled in the UK. It had flown in with the band from Los Angeles.

But many others in those staid, municipal concert halls were outraged and betrayed by their darling acoustic minstrel plugging into the mains. (It was, though no one realised it at the time, the birth of rock music as opposed to pop music). No matter that Dylan had released five electric singles – notably, “Like a Rolling Stone” – and one electric album in the previous 12 months: British audiences were still getting up to speed on his earlier records and they wanted back the Woody Guthrie protégé they’d seen in 1965.

This tension between artist and audience snapped in an almighty confrontation on the bootleg. Slow hand-clapping and jeering throughout Dylan’s electric half of the show – which was later properly identified as his concert at Manchester’s Free Trade Hall on 17 May 1966 and finally given official release by Columbia Records in 1998 – climaxes with one betrayed folkie letting fly with a long yell of “Judas!” It became the most famous heckle in rock’n’roll history.

Dylan is rattled, and for an awkward second the audience is stunned – until a yelp of solidarity with the heckler goes up. It is still a genuinely shocking moment. (Concert-goers in those days were routinely reverential.

They still stood for the national anthem at the end). Dylan eventually composes himself and leers: “I don’t believe you. You’re a liar!” And then, off mic: “You fucking liar!” (some claim he said: “Play fucking loud!”) before he and the band kick into the most majestic, terrifying version of “Like a Rolling Stone”, their final number – a performance of Gothic immensity surely drawn from Dylan by his anger at that single shout.

The concert, like many on the tour, was filmed by DA Pennebaker (who had also made Don’t Look Back). Against Pennebaker’s better judgement, he let Dylan himself edit the rushes into the film Eat the Document, which was never given proper release and is, even for Dylan obsessives, incoherent and unwatchable.

Now Pennebaker’s original footage from 1966 has been re-edited by Martin Scorsese and forms part of the Scorsese/BBC2 Arena co-production Bob Dylan – No Direction Home, to be screened next week. The thrilling news for those of us who consider Dylan in 1966 to have been at his most enigmatic and creative is that film of the Judas incident in Manchester has been found and will be seen for the first time in the Scorsese documentary.

In 1998, once Columbia Records had officially released the Free Trade Hall concert, I was able to make the radio documentary I had wanted to produce since the day I first heard that bootleg in 1978. And, more than anything, I was determined to track down the Judas man.

With fellow Dylanologist, Dr CP Lee – who had been at the Manchester show as a 15-year-old schoolboy – we assembled in the spooky, derelict Free Trade Hall about 20 veterans of that infamous night. Among them was a chap called Keith Butler, who’d come all the way from Canada, claiming to be the celebrated heckler.

The documentary, Ghosts of Electricity – Bob Dylan at the Manchester Free Trade Hall, was broadcast on Radio 1 early in 1999. Though I had no doubt Keith Butler had been there and joined in the cat-calling (he is, in fact, interviewed in the theatre foyer in Eat the Document, leaving the venue in a huff), I didn’t feel entirely happy about his claim to have made the historic heckle. Yet I had no evidence that it wasn’t Keith.

Then something strange happened. Soon after the transmission, I received an e-mail from a guy in Cumbria, John Cordwell, who’d heard the programme. The tone of his message was both wounded and bewildered, plaintive and plausible: “What puzzles me is why someone should falsely claim that it was they who produced the notorious ‘one-worder’. How do I know the claim is false? Simple; I was the one who stood up on the second balcony of the Free Trade Hall all those years ago and felt betrayed enough to give voice to my feelings.”

Others wrote in, too – some of them in green ink – but their claims contained either blatant historical inaccuracies or were suspiciously too detailed in their recall of a fleeting incident 33 years earlier. I was, though, intrigued by Cordwell and decided to go and meet him.

We came face to face for the first time in the King’s Arms in Salford, one afternoon in 1999. John was then a small, wiry 55-year-old with white hair and a short beard, wearing a denim jacket and round spectacles. He looked every inch the liberal child of the 1960s who might now be lecturing at a Manchester teacher training college. Which is exactly what he did.

He was affable, humble, slightly bemused and flattered by my curiosity and he visibly twinkled when we talked about music. I liked him instantly. (Over the next 18 months we became quite pally before his sudden and tragic death on 11 July 2001 from severe allergic shock, possibly a reaction to a number of stings from the bees he’d just started to keep.)

So, why – as a young Manchester law-student in 1966 – had he done it? “I think most of all I was angry that Dylan… not that he’d played electric, but that he’d played electric with a really poor sound system. It was not like it is on the record [the official album]. It was a wall of mush. That, and it seemed like a cavalier performance, a throwaway performance compared with the intensity of the acoustic set earlier on. There were rumblings all around me and the people I was with were making noises and looking at each other. It was a build-up.”

Had he arrived at the concert with the intention of causing a scene? “No. It came as a complete surprise to me. I guess I’d heard Dylan was playing electrically, but my preconceptions of that were of something a little more restrained, perhaps a couple of guitarists sitting in with him, not a large-scale electric invasion.”

But Dylan had had five electric hits in the UK by May 1966. Why should anyone have been surprised or outraged that he would be playing electrically? “Well, we were still living the first acoustic LPs and I don’t think many people had moved on to the electric material.”

But he’d had a huge hit with “Like A Rolling Stone” fully one year before… “It’s strange. But certainly that wasn’t the Dylan I focused on. Maybe I was just living in the past. And I couldn’t hear the lyrics in the second half of the concert [the electric set with the band]. I think that’s what angered me. I thought, ‘The man is throwing away the good part of what he does.'”

Had Cordwell come at this from a folk music background? “Yes.” Was he being encouraged by those sitting around him? Were others voicing their displeasure? “Oh, yeah. I think I was probably being egged on. I certainly got a lot of positive encouragement as soon as I’d done it. I sat down and there were a lot of people around me who turned round and were saying, ‘That was great, wish we’d have said that’ – those sort of things. And at that point I began to feel embarrassed really, but not that embarrassed. I was quite glad I’d done it.”

How did he feel about Dylan’s reaction? “I don’t recall that bit at all. I don’t recall hearing Dylan say anything back.”

This is bizarre. Dylan’s wounded response must have been clearly audible over the PA, although there were a few other heckles, semi-coherent, following Cordwell’s shout before Dylan hit back. One appears to call Dylan (or, indeed, Cordwell) “yer great pillock!” “Maybe I thought he wasn’t talking to me, or maybe the noise around me covered that up. I don’t know. I certainly don’t remember feeling I was having any kind of dialogue with Dylan.”

Why should anyone believe the Cordwell story? “No reason at all. Apart from the fact that it’s true.”

In the 20-odd years that this recording was available as a bootleg – and the most famous bootleg of all time – had he heard it? Was he aware of his own notoriety? “I never heard it until the [official] double album came out last year. I knew that there was [a bootleg with] a shout but, of course, I’d always assumed it was the Royal Albert Hall and someone else had done the same as I’d done.”

Only when Columbia released the live recording officially in 1998, confirming that the location was Manchester and not, as had long been assumed, London, did John Cordwell realise that he was, after all, the most famous heckler in rock’n’roll history. So when and why did he make the decision to “come out” after more than 30 years?

“It came at the same time as the revelation that someone else [Keith Butler] was claiming it was they that did the shout, and that intrigued me because I couldn’t understand why anyone would want to do that. I supposed I rationalised it by saying, well, maybe two people in the auditorium shouted ‘Judas’ but I’m absolutely convinced that it was me that the microphones picked up. And, being a bit of an amateur historian, I wanted to set the record straight.”

At this point, for some very unscientific voice analysis, I sent Cordwell to the very end of the empty lounge bar and asked him to shout “Judas” as he’d done on the night. The voice was identical. Judge for yourself when Ghosts of Electricity is repeated on Sunday.

How did he feel in 1999 about what he’d done back then? “I don’t regret doing it because I think I did it for the right sorts of reasons. I felt betrayed by someone who’d formed a very big part of my life for two or three years. But, y’know, with the benefit of hindsight, I don’t think I would do it now.”

And if he were ever to meet Dylan, what would he say to him? “Er… [long pause] I think I’d be embarrassed. And I think I’d be embarrassed if he could recall that concert. I don’t know that he will. But I’d say, ‘Look, a lot of water has passed under the bridge, I still like your music and, erm… you’re forgiven.” And he smiled mischievously.

And what did he think then, in 1999, of the electric set from Manchester on the official CD? “Brilliant [laughs]. Absolutely brilliant. But that wasn’t the set that you heard in the auditorium. It didn’t sound like that.”

![]()