Susan Meiselas has spent over five fearless decades at the frontline of history, photographing revolutionaries, teenagers and risque carnival dancers.

Photo: Six weeks at the frontline … a detail from Molotov Man, Estelí, Nicaragua, which appears in Mediations a the Jeu de Paume. Susan Meiselas/© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photosas/© Susan Meiselas/Magnum Photos

05 March 2022 | James Porteous | Clipper Media News

07 Feb 2018 | Sean O’Hagan | The Guardian

In 1971, at the age of 23, Susan Meiselas made a self-portrait in which she appears as a spectral presence, hovering on a chair in the living room of her boarding house in Massachusetts. The haunting double exposure, blown up larger than life size, is the first image you see as you enter Mediations, a retrospective of her work at the Jeu de Paume in Paris.

“That’s a total expression of what my psychology was back then and, to a degree, continues to be,” she says. “The present but almost invisible photographer.”

In the five decades since, Meiselas has earned a reputation as one of the greatest living documentary photographers, a chronicler of the lives of ordinary people caught in the turbulent tide of history. A large room in Jeu de Paume is taken up with In the Shadow of History, the epic Kurdistan project that took over her life for several years.

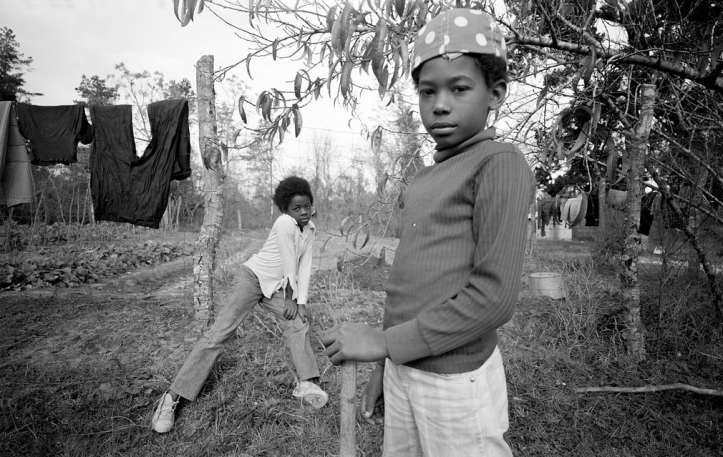

(Photo: Susan Meiselas)

Begun in 1997, it is a visual evocation of a people without a homeland. In places, it is almost overwhelming. The Kurdistan section uses her own images alongside short films, historical photographs, words and projections.

Susan Meiselas is an American documentary photographer. She has been associated with Magnum Photos since 1976 and been a full member since 1980. She is best known for her 1970s photographs of war-torn Nicaragua and American carnival strippers.

Wikipedia

On one wall, a giant map of the world shows all the places where Kurdish diasporic communities have formed. Chains hang from each location, bearing clusters of handmade laminated books in which photos from family albums are accompanied by testimonies of suffering and flight.

These were made just a few days before the exhibition opened, in a workshop with Kurdish people who have settled in Paris. “They brought their photographs and their memories,” she says Meiselas. “In this way, the work grows each time it is exhibited.”

Nicaragua, her best-known series, made during and after the Sandinista revolution, attests to the sustained relationships she develops with her subjects.

Having spent six weeks there in 1979, Meiselas returned in the early 1990s to make Pictures from a Revolution, a documentary film in which she tracked down people in her original photographs. In 2004, she went back again to work alongside locals in creating memorial sites using her images on murals, a project documented in another film, Reframing History.

“In all my work, I form a relationship,” she says, “and the title of the retrospective is to do with my belief that photography is an act of mediation between myself and the subject. The camera allows me into places I would otherwise not have gone and helps create deep engagements.”

In places, Mediations is almost overwhelming. The Kurdistan section uses her own images alongside short films, historical photographs, words and projections. On one wall, a giant map of the world shows all the places where Kurdish diasporic communities have formed.

Chains hang from each location, bearing clusters of handmade laminated books in which photos from family albums are accompanied by testimonies of suffering and flight. These were made just a few days before the exhibition opened, in a workshop with Kurdish women who have settled in Paris. “They brought their photographs and their memories,” says Meiselas. “In this way, the work grows each time it is exhibited.”

Born in Baltimore in 1948, Meiselas studied “visual education” at Harvard. As a child, she became curious about photography after her father gave her his army camera. Later she took a part-time course with the great American landscape photographer Ansel Adams. Another formative experience was working as a film editor for Fred Wiseman on his groundbreaking 1971 documentary Basic Training, which looked at how raw military recruits are turned into disciplined soldiers.

Meiselas’s early black-and-white work, which tends towards quiet observation, is one of the surprises of the exhibition. Her first series, 44 Irving Street, began in 1971 while she was still at Harvard. It comprises portraits of her neighbours in the apartment block where she lived. Each is accompanied by a piece of writing by the sitters about themselves. “I think it’s nicer than most rooming houses (no dirty old men),” writes Joan, adding: “I don’t think the photo of me really gives the essence of me.”

Meiselas recalls plucking up the courage to knock on her neighbour’s doors, and her discomfort at having to direct them for the portrait. “When I started out, I was awkward and a bit shy. I had to work out what photography could be for me. I was certainly not influenced by the street photography of the time. It felt too confrontational. I had to develop my own language of reportage.”

Prince Street Girls, a series begun in 1975, chronicles the lives of a group of pre-adolescents from New York’s Little Italy. After she moved into an apartment in their old school house, Meiselas befriended the girls (and one boy called Frankie) over a few years and still keeps in touch, though these days they are scattered across the outer boroughs. “Their daughters now want to see the photographs,” says Meiselas. “Sometimes the women come back into Manhattan, but they are sensitive about how little of their neighbourhood is left.”

Her breakthrough 1970s project, Carnival Strippers, is also in the retrospective. These intimate black-and-white portraits of the performers in a risque travelling show have lost none of their raw power. The girls thrust their hips at the punters who gawp back and, in some instances, grab and paw them. Meiselas photographed the women from the men’s point of view and the men from the women’s, as well as capturing the performers relaxing between shows.

“I don’t think a man would have gotten entry to the inner sanctum of the dressing room in the same way,” she says, “or indeed taken photographs in the same way. Now, of course, the girls would be taking photographs of themselves and disseminating them on social media.”

When Meiselas became a Magnum photographer in 1976, she was one of five women. Today there are 13. In all its attempts to reinvent itself of late, it remains a predominantly male institution.

“I can’t deny that,” she says. “And I’ve seen the comings and goings of women who have been involved. It’s a complicated issue. Do I want to say, ‘I’m a woman photographer and that’s what validates my view on the world?’ Really? Is that it? But, on the other hand, I do speak from a different perspective. I do have a different approach. Part of my role is to be a mediator, someone who brings people together.”

She pauses. “People often ask me, ‘Why do you do it?’ Perhaps the more important question is, ‘What are they getting from it?’”

Susan Meiselas: Breaching Boundaries in Photography

03 July 2018 | James Estrin | New York Times

Susan Meiselas, who joined Magnum Photos in 1976, is also the president and co-founder of the Magnum Foundation. Born in 1948 and starting as a teacher in the South Bronx, she went on to produce a definitive chronicle of Nicaragua’s Sandinista revolution. More recently, she has led the foundation’s efforts to nurture a new, diverse generation of photographers. Her books include “Carnival Strippers,” “Nicaragua,” and “Prince Street Girls.”

In the last year, she has also been the subject of two books, “Susan Meiselas: Mediations” (Damiani) and “Susan Meiselas: On the Frontline” (Thames & Hudson). She spoke with James Estrin about her career. The conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

In “Mediations,” other people are writing about you, and “On the Frontline” has text from a conversation between you and Mark Holborn.

The two books came out almost simultaneously in the past year, but they’re completely different. “Mediations” is the catalog for the recent show at the Jeu de Paume in Paris and is going to be at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art this month. It’s not so much a catalog in the classic sense of showing the work on exhibit as it is focusing on the ideas in the show. “On the Frontline” is about process and being a documentary photographer.

It’s interesting because you become an object, your life becomes an object, in two very different ways. One comes from a conversation where I’m speaking with Mark about my own process. And the other has other people writing about you. I’m present through the photographs, but it’s their reflection on my work.

How does it feel to be discussed and analyzed in an academic or curatorial manner, particularly for someone who’s more than capable of talking for herself?

Honestly, the more you are in conversation, you think about your own process, and that’s a way to grow.

I never defined myself in one particular way. I don’t call myself a color photographer, and the formal qualities of my work can shift. The mediums can shift. The focus of my lens shifts.

I’m working from within, for the most part, from what might draw me and what might dwell in me, what might sustain me or my interest. I’m trying to make sense of each work, and sometimes when you go back you make sense better than in the midst of some project.

Why is it important to have that kind of examination, whether through someone else’s eyes or your own?

It contributes insights that I feel give me self-knowledge.

I didn’t seek to do this show. Marta Gili at the Jeu de Paume called me a couple of years ago and asked. It’s a big endeavor and it takes time and work, not just for myself but also my assistants. I’ve done psychological digging; they’re doing archaeological digging in my archive.

It’s been a valuable process. Pia Viewing wrote a piece in “Mediations,” she was looking at the work and she said, “I see place in so much of your work.” Of course I can see it, too, but I’ve never said that. It might be the guiding principle that I begin with, but I now see how I have always found some sense of boundaries to a place that’s enabled my work to feel focused.

Even though Nicaragua is a relatively small country that I could drive across in several hours, it’s a place that I can come to know, even with all the turmoil. And to some degree you could even make that case about Kurdistan, where there is a much more complex psychological, social historical set of forces, especially with the archiving of a hundred years of history. But still, it’s place. It’s all about wanting and believing that they need and should have a homeland.

So when you start doing your projects, and you’re 25, you’re not setting out with an idea of a career or overarching themes.

I didn’t even have a self-defined notion that I’m a photographer at that time. It evolves. I was teaching at an elementary school in the South Bronx that was unusual because the superintendent was very progressive and wanted to experiment; these were kids that were coming from many different cultures.

I had studied childhood education at Sarah Lawrence, and this was the day of Marshall McLuhan, in which people were thinking about how cameras can engage kids in learning. I did that for 3 to 4 years, first in the South Bronx, and then in the South. So my migration to becoming a photographer began with being engaged by photography through teaching.

The carnival strippers changed all that because suddenly I am being the photographer. In the early ’70s I’m wandering around the streets, looking at people and trying to figure out what to make photographs of, but I don’t really have a centering point for my own work until “Carnival Strippers.” Suddenly, there’s a reason for me to be there. I understand what I’m connecting to. It’s integrating all of the ideas of being a young woman in that period of early feminist thinking.

If that Susan Meiselas, the teacher and photographer who started “Carnival Strippers,” were 25 years old today, what would she be doing?

Well, I know what I wouldn’t be doing: I’m not as obsessed with self as much of the culture is. So I don’t think that fundamentally would have changed.

I’ve taught with the Magnum Foundation social justice program with Fred (Ritchin) and with other programs, and I’ve helped answer that question for other 25-year-olds more than for myself.

In terms of training — which I didn’t have the opportunity for when I was that age — I think a program like the Interactive Telecommunications Program at N.Y.U. is exciting. If I were to go on as a graduate student, that’s where I think I would have found the edge in thinking that changes us or challenges us to think about new ways of relating through the photographic image, or connecting inward in maybe even more surprising ways.

I didn’t choose to join the Peace Corps when I was 25. I placed myself in the South Bronx. So I was not inclined to just go as far away as most people would think. So I might be even more immersed in a community.

What is interesting to me is that your impulses probably would have been the same.

When I’m working with young people, I think of how much more they have, yet they often feel they have so much less than we had. As I became part of the Magnum community, I was more exposed to the myths of Capa and the real life of Cartier-Bresson and realized I was in a community that I knew nothing about before I entered it. They had a very different set of opportunities than we had at that time, in the mid to late ’70s. Maybe every generation feels that.

What are the opportunities that this generation has?

Well, I think they’re not as confined by gatekeepers. That’s a huge difference. The web is challenging because you still have to be distinctive on it. You have to figure that out, but people have.

People have created sharing platforms that are collectively driven and may not have monetary value, so they have to have alternative strategies for the economic transactions that they need to also benefit from. This is a whole open landscape for imagination.

Even the look-and-listen app with the last Nicaragua book was an attempt to try and shift the way we experience subjects in photographs and create the channel for their voice to bridge this terrible distance that can still exist in photographs.

When did you join Magnum?

I had a very small assignment from Harper’s to photograph women at the 1976 Democratic convention. If you’re major media, you get a pass, or multiple passes, and you can move freely. But if you’re a small international or national publication, you only get a rotating pass for 15 minutes. You barely can get on the floor and do any work before you have to give up that pass.

I was agonizing because it was one of my first assignments and I was failing. I just couldn’t make the photographs I was hoping to because of the system. I went up to the guy running this and said: “Look, this isn’t working for all of us on the line and we’ve got to change the system. Even if we only had a half-hour we could produce something.” Gilles Peres happened to be near and asked if I wanted to borrow one of the passes he had. I said, “No, I want to change the system.” So he loved that.

I wasn’t on the path of becoming a professional photographer. I didn’t really have at the time a sense of Magnum, its history or what it would mean to join a cooperative. He asked me what I was doing and I had this portfolio of work that I brought up to Magnum and they asked if they could propose me in their upcoming meeting.

Well, you’ve always been a troublemaker.

Ah, thanks a lot, I don’t think of myself as a troublemaker, I just think of myself as trying to think out of the box a bit. Sometimes getting boxed in kills the spirit.

You grow by breaching those boundaries and by not being constrained by what other people think you are or should be. You have to sustain that within yourself because very often you don’t get the support, the external support.

A lot of the work of Magnum Foundation, for me, is helping to create a supportive community. And helping young, emerging and diverse voices feel that they can find others and create networks with other possibilities through us and with us but beyond us.

You seem fascinated by collaboration. You brought the carnival strippers’ voices into the story from the beginning.

The women saw the contact sheets every week. I wanted them to see how I was seeing them, and they influenced to some degree the images I made. I made portraits really for them, not because I wanted to make portraits, per se. Some of them saw my final transcript that I was editing, commented and actually changed some of it. That’s an ideal process.

Using audio and collaborating with the strippers, as well as your later collages, are strategies that are current in documentary photography. The Magnum Foundation has, in workshops and programs, focused on these kinds of actions, haven’t they?

I think the foundation reflects a lot of the concerns. I didn’t honestly have the community when I was doing that work that we’re trying to build now. It was harder to do some of the work I was doing, so much lonelier. It was not as well understood at the time. Now people integrate archival photography organically, but when I was doing that work in ’91 in Kurdistan, my colleagues were challenging me, asking, “Why are you reproducing someone else’s historical photographs and not making your own contemporary images?” There were people in the art history field who were challenging me that I didn’t belong curating history.

So one has to resist, and respond to, one’s own instincts. Part of my thinking is trying to build the foundation for new thinkers, which involves community opportunities with new tools like VR360 and augmented reality.

Why is it important today that photographers innovate?

I’m not saying it’s important for everyone. It may not be.

But it shifts the way you see the work. So I think all of these are avenues of shifting and re-engaging us in work. And it doesn’t have to be about technology. People have done this with text. I happen to have been more drawn to sound and voice. It’s just building a broader vocabulary to give a viewer a richer experience.

Which is an exciting thing, but it’s also necessary because it can be very hard to effectively communicate and engage an audience today.

That’s the biggest challenge, and we can’t just assume that a photograph we’ve made does that inherently. We may hope it will. But I’ve always said that the work for a photographer is not just making photographs, it’s making the space for their photographs to be seen and experienced.

When you were starting out, there were fewer women doing the kind of photojournalism you were doing in Nicaragua.

In Nicaragua there wasn’t another woman photographer when I arrived in June 1978 during the insurrection. There were women — a few women writers and television producers.

The next year Cindy Karp came, and then Donna DeCesare, and Corinne Dufka followed her. I think we all encouraged each other. In the early ’80s there were Europeans and the Nicaraguan women photographers Margarita Montealegre and Claudia Gordillo.

I didn’t know about Dickey Chapelle. I should have. I didn’t even know about Catherine Leroy. I could have, but I didn’t. I did know about Lee Miller, and the women in Magnum before me, but they were not focused on wars.

I’m excited now as I collaborate with women in Magnum, and there are so many more women doing work, not necessarily the same kind of work I do, but that’s the exciting thing, they’re taking their own visions in different directions.

The Magnum Foundation has been effective in fostering and promoting a diversity of voices from all over the world.

That’s been the priority. That’s exactly its intention. I just had someone who came from Saudi Arabia and told me how stunned they were to see Tasneem Alsultan’s work in The New York Times.

Well, she was a wedding photographer, in an open submission process, when we brought her through the Arab documentary program and she had six months of mentoring before you see her in The New York Times.

We also know this isn’t just about careers. This is about keeping a set of values coherent.

What do you mean?

We can point to more diverse voices, but we also are living in a society that has more separated cultures that don’t intersect as well. We believe that photography is a means by which that can happen. It has to do with intention, collaborative relationships and acknowledgment of differences.

The person who is your subject is not your object.

I think this is a very important idea for people to think about. Do we objectify aesthetically or formally? How do we give appropriate presence and dignity to that subject? They are not there just for the lens of the other.

Follow @nytimesphoto on Twitter. You can also find Lens on Facebook and Instagram.

![]()