30 March 2021 | STEVE MARBLE | Los Angeles Times (original link)

G. Gordon Liddy, the tough-guy Watergate operative who went to prison rather than testify and later turned his Nixon-era infamy into a successful television and talk show career, has died at age 90.

Liddy died Tuesday at his daughter’s house in Virginia, his son Thomas P. Liddy told the Associated Press. He did not give a cause of death.

While others swept up in the Watergate scandal offered contrition or squirmed in the glare of televised congressional hearings, Liddy seemed to wear the crime like a badge of courage, saying he only regretted that the mission to break into the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters had been a failure.

He drove around Washington in a Volvo with license plates reading H2OGATE, openly discussed the botched burglary on talk radio and late-night TV, took villainous television roles that seemed to trade on his soiled reputation and mocked his fellow Watergate operatives as bumblers.

“I was serving the president of the United States and I would do a Watergate again — but with a much better crew,” he said.

Tight-lipped, Liddy refused to testify at either the Watergate hearings or at his own criminal trial, accepting his fate and a 20-year prison term. “My father didn’t raise a snitch or a rat,” he explained to the Los Angeles Times in 2001.

But when his sentence was commuted by President Carter and he was freed after 52 months in prison, Liddy couldn’t stop talking.

He became a sought-after public speaker, a far-right radio talk show host who called himself the “G Man” — “This is Radio Free D.C., and I’m G. Gordon Liddy” — and a prolific writer. He also fit comfortably into the skin of TV villains, playing a recurring bad guy role on “Miami Vice” and similar characters on “MacGyver” and “Airwolf.”

“I played only villains, and that way, as Mrs. Liddy says, I don’t have to act. I just go there and play myself,” he told Playboy magazine in a 1995 interview.

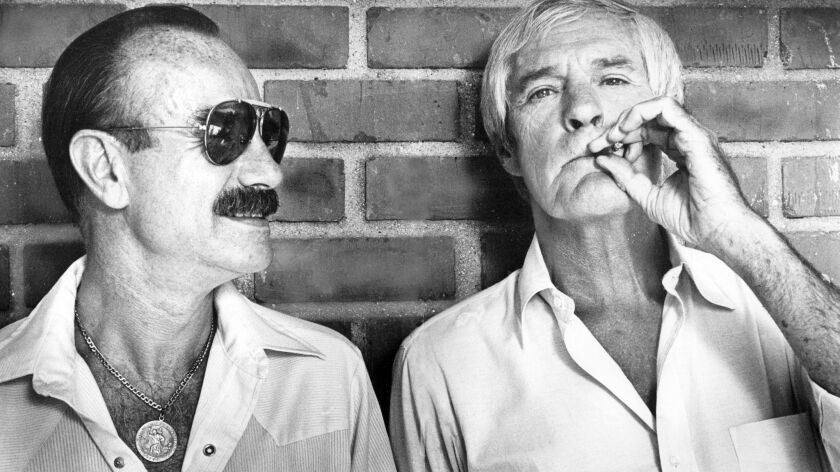

(Iris Schneider / Los Angeles Times)

He was born George Gordon Liddy in Hoboken, N.J., on Nov. 30, 1930. He recalled an overwhelming sense of fear and dread as a child — the hulking dirigibles that flew silently over his house, the rats that skittered along the electrical lines, the nuns who would berate him at school. He claimed that the first reassuring voice he heard was that of Hitler.

“Hitler’s sheer animal confidence and power of will entranced me,” he recalled in a 2004 interview. “He sent an electric current through my body.”

Liddy would often cite the nearly sadistic tests and challenges he claimed he put himself through to toughen his will, some straining the boundaries of credibility: standing in front on an ongoing train and jumping from the tracks at the last minute or climbing a tree during an electrical storm to see if he would be struck . Later, he would famously describe how he won the confidence of his Watergate associates by holding his palm over a candle flame until his skin burned.

He joined the Marines but never fulfilled his dream to fight in the Korean War. Instead he went to law school, became an FBI agent and then a prosecutor. When he ran for a New York congressional seat, one of his favorite campaign ploys was to peel off his jacket before he spoke, revealing the shoulder holster he was fond of wearing. He lost the campaign and joined the Treasury Department, where he was remembered as a troublesome employee and ultimately let go.

That led Liddy to the White House and a clandestine unit known as “the plumbers,” whose first assignment was to discredit former defense analyst Daniel Ellsberg, who had leaked the so-called Pentagon Papers, leaving President Nixon smarting. Hoping to find something that would undermine Ellsberg’s credibility, Liddy and the others broke into the office of a Beverly Hills psychiatrist who had been treating Ellsberg. They came away empty-handed, though undetected.

From the start, Liddy seemed eager to do what was needed to get Nixon reelected. In “Will,” his 1991 autobiography, Liddy explains that in meetings with the plumbers he came up with an assortment of potential plans to bolster the president — break-ins, wire-tap jobs, counterdemonstrations and even a scheme he called “Sapphire,” in which escorts would be hired to lure powerful Democrats to a rented houseboat in Miami Beach where their intimate conversations and actions could be recorded.

Liddy said that as he shared his plans with Nixon’s associates, the idea that quickly gained traction was to break into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate in Washington and tap the phones, review files and photograph revealing documents. The first burglary was a success, but when the team returned to adjust microphones and add additional listening devices, it all unraveled.

A security guard noticed that someone had put tape over a self-locking door at the office and residential complex, and five people were arrested at the scene. Liddy, who had kept his distance from the actual dirty work, was later indicted as the mastermind of the scheme.

After his conviction, Liddy said he alternately worked on his autobiography and on staying alive during his five years behind bars. He told the Washington Post in 1979 that for protection he armed himself with an ax handle attached to a jagged piece of steel and a sharp-edged steel bar.

“I don’t believe in being a victim,” he said.

When his sentence was commuted and he became a free man, Liddy repackaged himself as a showman. He did radio and he did television, he spoke on college campuses with LSD guru Timothy Leary, and he pitched corporate chiefs on the value of hiring the commando-style security team Hurricane Force he planned to form.

Brash, pointed, funny and brimming with stories — some believable, others less so, he earned up to $12,000 an appearance. He told listeners he still admired Nixon, thought liberals were ruining the country, didn’t regret Watergate, approved of group sex and believed it fair that he went to prison.

“I broke the law,” he told the crowd during a speech at George Washington University. “I took a risk and lost.”

(Getty Images)

In 1992, Liddy became the host of “The G. Gordon Liddy Show,” four hours of radio talk fare in which the host swung from a matter-of-fact reading of the daily news to bombastic outbursts. He told listeners he had used photos of Bill and Hillary Clinton for target practice to improve his aim and spoke firmly about the need to be skilled with weaponry for self-protection.

“I love my home so much,” a caller on WJFK told him, expressing concern about being burglarized.

“Then protect it. Get a shotgun,” he advised. “After you kill him, say a little prayer for his soul. You won’t want to be brutal.”

For his occasional role on “Miami Vice,” Liddy shaved off what hair he had but kept his bushy dark mustache. The look was properly sinister. But the hair never returned, the mustache turned white, and his short, stocky frame eventually gave way to a stooped, frail figure.

Liddy also tried to change the Watergate narrative.

The accepted version of the break-in — from Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s “All the President’s Men” to the national archival material at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library — put the blame directly on the White House, where some of Nixon’s most trusted signed off on a plot to slip into the Democratic headquarters and plant the necessary devices to listen in as their opponents drew up election game plans.

Liddy initially said he went to prison accepting that version, too.

But later, the Watergate mastermind said he began subscribing to a theory that has been advanced by a far lesser known pair of journalists, Len Colodny and Robert Gettlin, the authors of “Silent Coup.” The book, published in 1991, shifted the blame, putting it squarely on former Nixon White House Counsel John Dean.

The burglary, Liddy began telling listeners on his radio show, was motivated by Dean’s feverish concern that the Democrats had evidence that his girlfriend and future wife had a connection to a woman who was running a call-girl ring.

The book was dismissed by scholars as revisionism. Woodward brushed it off as fiction. “A scandalous fabrication,” said Alexander Haig, Nixon’s former chief of staff. “Garbage,” Dean said.

Dean, whose testimony during the Watergate hearings helped bring down the president, sued for defamation, as did a Louisiana schoolteacher who briefly worked as a secretary at the Democratic Committee headquarters at the Watergate hotel. The book suggested she helped arrange dates between visiting Democrats and escorts.

The trial in Baltimore became a fresh battleground to settle old scores.

“This,” Liddy testified, “was a John Dean op.”

During the trial, nearly every brick in Liddy’s account of Watergate was chipped away. The Los Angeles Times reported in 2001 that one of the sources who had provided information to the book’s authors acknowledged that he had mental disabilities, took a variety of medications and had a drinking problem. He testified he had little memory of the details of Watergate and no memory of the secretary who’d been linked to the supposed call-girl operation.

But both suits were dismissed and the book’s publishers reached an out-of-court settlement with Dean.

But under all the brass, there could be a softer side to the person Nixon once described as “the most dangerous man in America.” A Washington Post reporter who spent a late afternoon in 1992 at Liddy’s home on the Potomac found him to be just another grandfather, someone who dutifully rearranged the cars in the driveway when his wife came home, cheerfully discussed plans for finding a painter for their house and bantered about with the grandkids.

In a 1997 appearance on “Late Night with Conan O’Brien,” Liddy — there to pitch a wall calendar of barely clad women armed with high-powered weaponry — seems jovial and light, even as he demonstrates on fellow guest Don Rickles how he could quickly and effectively kill someone with nothing more than a pencil.

Colodny, the journalist and author, was unsure whether Liddy was fully satisfied with his post-Watergate life.

“I think he would have liked to have done something more serious with his life,” he said.

Liddy is survived by five children and 12 grandchildren. His wife of 53 years, Frances, died in 2010.

![]()