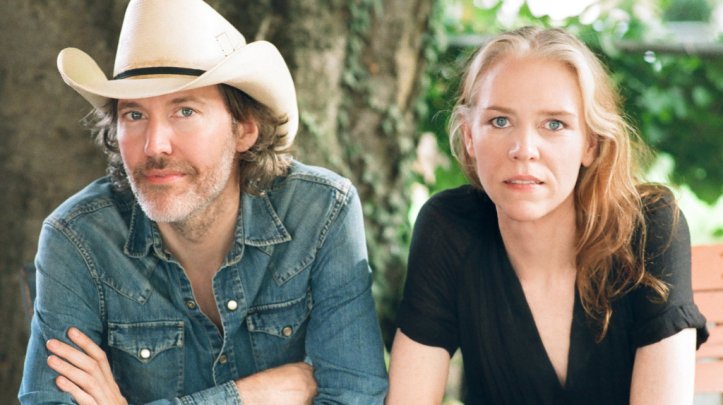

Henry Diltz/Courtesy of the artist

08 March 2021 | James Porteous | Clipper Media |

https://linktr.ee/jamesporteous

“Orphan Girl”

I am an orphan on God’s highway

But I’ll share my troubles if you go my way

I have no mother, no father

No sister, no brother

I am an orphan girl

I have had friendships pure and golden

The ties of kinship have not known them

I know no mother, no father

No sister, no brother

I am an orphan girl

Watch Video Below

But when He calls me I will be able

To meet my family at God’s table

I’ll meet my mother, my father

My sister, my brother

No more an orphan girl

Blessed Savior make me willing

Walk beside me until I’m with them

Be my mother, my father

My sister, my brother

I am an orphan girl

I am an orphan girl

Source: LyricFind

Songwriters: Gillian Howard Welch

Orphan Girl lyrics © Universal Music Publishing Group, BMG Rights Management

Behind the Song: Gillian Welch, “Orphan Girl”

RICK MOORE | “ABOUT A YEAR AGO” | American Songwriter

Since Gillian Welch arrived in 1996 on the still-developing roots music scene with her debut album, Revival, her name has become synonymous with quality in singing and songwriting. Usually working (and often co-writing) with her musical partner Dave Rawlings, under her own name and as part of the Dave Rawlings Machine, Welch is today one of the genre’s most respected figures.

“Orphan Girl,” written solely by Welch, was the opening track of Revival, which was produced by T Bone Burnett. She would later work with Burnett on the O Brother, Where Art Thou? movie soundtrack, which introduced Americana, country and bluegrass to a segment of society that had previously had no clue about this music.

While Welch became renowned for vocal work that was straight outta Appalachia, “Orphan Girl” actually sounds like a song that could have been written there as well.

“Orphan Girl” is sung from the point of view of a woman who, well, has no family, and is asking God to one day unite her in Heaven with her relatives. She doesn’t sound particularly grief-stricken about her lack of a family, and even admits to having had great friends and relationships. But she still longs for that day when she will be with her blood relatives. The lyric is beautiful in its simplicity, and couldn’t be much more concise and to the point, using only the necessary words to open the story:

I am an orphan on God’s highway

But I’ll share my troubles if you go my way

I have no mother no father no sister no brother

I am an orphan girl

And she beseeches Jesus to watch over her until the day comes that she meets her family:

Blessed savior make me willing

And walk beside me until I’m with them

Be my mother my father my sister my brother

I am an orphan girl

Welch discussed the writing of the song with writer Molly Morgan at PasteMagazine.comin 2016. “I have this weird thing where I write from kind of an unself-conscious place where I don’t even know I’m writing something really, really personal when I’m writing it … When I wrote ‘Orphan Girl,’ I didn’t realize that it was autobiographical. Because I’m not an orphan, I’m just adopted. But I didn’t realize when I started this song called ‘Orphan Girl’ … It’s so easy to look at it and go, ‘Oh that’s her story.’ Well, it is, but I wasn’t setting out to do that. I don’t even know what I’m doing. It’s kind of like the song is a dream. You have the dream, and you don’t realize that you know exactly what it’s about until you’re telling someone the next day. That’s what the songs are like. I don’t realize that I know exactly what it’s about until it’s done.”

Welch’s name as a writer was already getting around in musical circles before the release of Revival. “Orphan Girl” was first cut in 1994 by brother and sister bluegrass duo Tim and Mollie O’Brien, and was recorded in 1995 by Emmylou Harris for her classic Wrecking Ball album. In addition to the track on Revival, you can also find two alternate versions of the song (including the original home demo) on Welch’s album Boots No. 1: The Official Revival Bootleg.

David Gahr*

How Gillian Welch, David Rawlings Turned Prolific After Nearly Losing Their Life’s Work

31 July 2020 | JONATHAN BERNSTEIN | Rolling Stone

The first catastrophe of 2020 came slightly earlier than most for Gillian Welch and David Rawlings. On a stormy evening in early March, the couple found themselves racing around Woodland Studios — the historic East Nashville recording facility that’s served as the duo’s home base since 2001 — trying to rescue their life’s work after a direct hit from a tornado. Their master recordings, instruments, and gear were all threatened by the rain pouring into the building for the past four hours.

“Everything got wet,” Welch says. “You wouldn’t want to see the tape boxes. They’re a horror.”

Welch and Rawlings were able to salvage mostly everything from their damaged studio, but the deadly Nashville tornado, as well as the coronavirus pandemic that it preceded by little more than a week, has instilled in the pair a renewed sense of urgency to release music both new and old.

On Friday, the duo unveils Boots No. 2: The Lost Songs, Vol. 1, the first installment of a batch of 48 demos that Welch and Rawlings recorded during one unimaginably productive weekend in late December 2002. That release comes two weeks after All The Good Times, a surprise collection of homespun folk covers cut over the past few months in quarantine.

“Dave and I are working as hard as we can to put as much music into the world as we can,” says Welch. “That’s basically our modus operandi right now.”

As Welch and Rawlings explain in an interview with Rolling Stone, part of that dedicated, urgent approach comes from the experience of nearly losing their master recordings in the storm. Part of it also comes from the more practical financial concerns of needing to repair their damaged studio, as well as being small-label owners and artists who earn an income primarily on the road. “It’s kind of madness, honestly,” says Rawlings of the pandemic’s disastrous effect on their livelihood.

And finally, part of their release-as-much-music-as-possible mindset stems from what Welch and Rawlings both describe as an intensified emotional draw toward the folk songs they’ve spent their whole lives playing.

“Music has some things that only music can do in a time like this,” Rawlings says. “With folk songs, every person has put a little bit of their DNA into what becomes the bloodstream of that song, and the culture and time period they came out of usually did also. It’s what keeps songs and melodies [alive]. They put some of themselves and their own experiences into the song. [Playing these songs] in a time of isolation and reflection, it’s almost like all those people are there.”

You’re releasing the first 18 of 48 demo recordings that you made between 2001’s Time (The Revelator) and 2003’s Soul Journey. That’s a lot of music to write in just a few years.

Welch: It wasn’t even a couple years, it was just a weekend. But they weren’t written from scratch. I have workbooks of song ideas and unfinished songs, lots of them, somewhere between 100 and 200 notebooks. So it’s not like we thought of all these songs in one weekend, but we finished them and recorded them in that time.

When was this weekend? Were you starting work on Soul Journey?

Welch: This was earlier. It was in December 2002. My publishing deal was going to renew automatically on January 1st. I owed them songs. I’d been a writer tied to a publishing deal since January 1st, 1994. We had become this touring act, and I don’t write on the road, so I owed them all these songs. Dave said, “What if we catch you up? What if we turn in all the songs?” He started pulling notebooks out and we started finishing songs. I’d finish one, he’d look in the notebooks for another song, I’d finish another, and when he’d come back with the next song, he’d turn the tape machine on and I would sing it once and we wouldn’t listen to the performance. That’s what happened. The songs fulfilled my requirement, and then I was no longer a staff writer.

What do you hear when you listen back to these nearly 20-year-old demos?

Welch: It’s not our normal process by any stretch. Dave and I, we’ve always been album-oriented artists. These were very different. These were recorded very un-self-consciously. These songs have this weird immediacy, and I hear this complete lack of filter. I can hear that I’m not judging myself. It was just: “We wrote this song, now we need to record it.” There are things you think about when you know you’re making a record: “Is this the best version of the song? This is the version people are going to hear.” There was none of that with this.

How long had it been since you revisited those tapes?

Welch: Every now and then there’d be a reason. Buddy Miller called us up at one point. He was making a record with Solomon Burke and wanted to see if we had any country-R&B songs. That’s how Solomon ended up doing “Valley of Tears.” Alison Krauss, same thing. She was looking for some songs and she ended up doing “Wouldn’t Be So Bad.” But to be perfectly frank, this record is definitely a response to what’s been happening, in that we decided to put it out now.

How so?

Welch: The tornado was a big reason. Having all the tapes almost destroyed really makes you think. All of our masters were in the tape vaults at Woodland, and when the roof got peeled off like a sardine can and then it rained for four hours and then the ceilings all collapsed, basically everything we have was almost destroyed. … It made us think about our whole archive. It’s one thing to know in your mind that you have these tapes, and it’s another thing to run through the dark with them in your arms, rescuing them from destruction. Once we rescued them at great peril, you think, “Why did I rescue this?” And then you find yourself thinking, “Well, I guess because it means something.”

What compelled you to record an album of cover songs in your living room during quarantine?

Welch: A lot of artists I know are struggling with the feeling of futility. I know I myself was feeling really non-essential. The artists I know, we had really gone into a post-traumatic survival mode. But I actually was hearing from quite a few people that the only bright spot was music. So for me, that really helped me focus. Dave and I, in all the disarray, what did we do? We sat and played folk songs every night. That was our response to this moment.

Rawlings: I wouldn’t say that we played more music [than normal], but I might say that the music meant more. It did feel good to capture a few things, wherein in the past we might play a song sometimes and I’d think, “I wish we weren’t the only two people in the world who’d ever hear that performance, because that sounded like it had something.”It’s not like that happens every song, it certainly doesn’t. But maybe once a night or once a couple nights you play something, and you go, “Jeez…”

Whose idea was it to actually record the folk songs you were playing each night?

Welch: I largely live in my head most times, and the past few months, I’ve just been completely unmoored from the world. Would I have had the wherewithal to set up a microphone and put tape on the machine? No. But Dave does. Likewise, with the 48 lost songs, those notebooks don’t get pulled out, those songs don’t get finished, without Dave saying: “I think we can do this.” This is why we’re still partners, because we both recognized, long ago, that we make better art working together. Those 48 songs would have gone into the ether. Same with “Miss Ohio.” I was singing and he heard me through the door. I thought it was just this silly rhyme, like a nursery rhyme. And Dave said, “What was that one?” I was like, “Which one?”

Rawlings: I overheard her running through stuff, and then I remember we were talking about some other song we were trying to write, and I was like, “What was that other catchy thing you were humming?” She was like, “Oh, I don’t know, it’s just this little ditty.” And it was the top of that chorus [to “Look at Miss Ohio.”] It’s funny how songs have that kind of elemental power in retrospect but they can seem so small upon first hearing. You almost think: “Oh, well that’s been done.” Or you think, “That’s just an earworm.” And then the song starts running around.

The image you both conjure is of two people who perpetually spend their time playing folk songs for themselves. Have you found any time to relax during the past five months? Do you watch Netflix, like the rest of us? Are you writing new music?

Rawlings: I’m not much of a relaxer. I mean, 14-hour days are pretty normal. But it has to be at this point, with everything that’s going on here. There’s been a lot of technical work. You have to keep the music rolling. I look at the arc of our career, and we caught the very end of what we’d consider to be the music industry, pre-collapse. Pre-pandemic. And the only way forward was to do things yourself, to be an independent label. I don’t always know that it’s for the best, but it is what it is.

Welch: Most of the writers I know, particularly the top-shelf ones, things are pretty quiet right now. Everybody is still reeling from this cataclysmic sea change. My writer friends, my artist friends, we’re keeping each other close right now. After the, “How are you doing’s?” it’s always, “Are you writing?” We’re always like, “No man, not a chance. Nothing.” There’s comfort in that. So we’ve been focusing on playing, just playing and singing and diving into the canon of folk songs and really connecting with them. Finding something in them, possibly more than ever. Because they’re diamonds. They’re indestructible.

![]()