Bettmann/Getty Images

02 May 2021 | James Porteous | Clipper Media

Zoot Suit Riots

SEP 15, 2020 ORIGINAL:SEP 27, 2017 History.com (original link)

The Zoot Suit Riots were a series of violent clashes during which mobs of U.S. servicemen, off-duty police officers and civilians brawled with young Latinos and other minorities in Los Angeles. The June 1943 riots took their name from the baggy suits worn by many minority youths during that era, but the violence was more about racial tension than fashion.

What Is A Zoot Suit?

During the 1930s, dance halls were popular venues for socializing, swing dancing and easing the economic stress of the Great Depression. Nowhere was this more true than in the uptown Manhattan neighborhood of Harlem, home of the famed Harlem Renaissance.

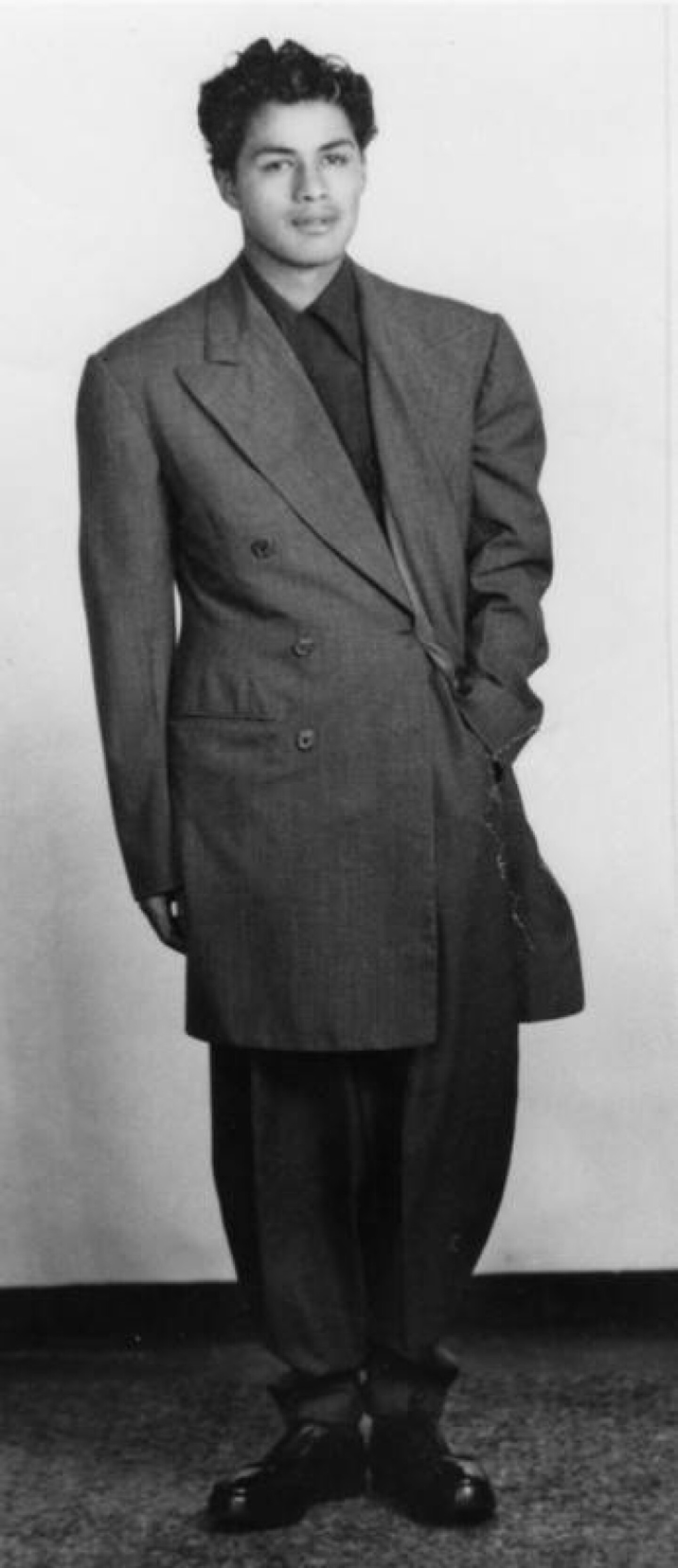

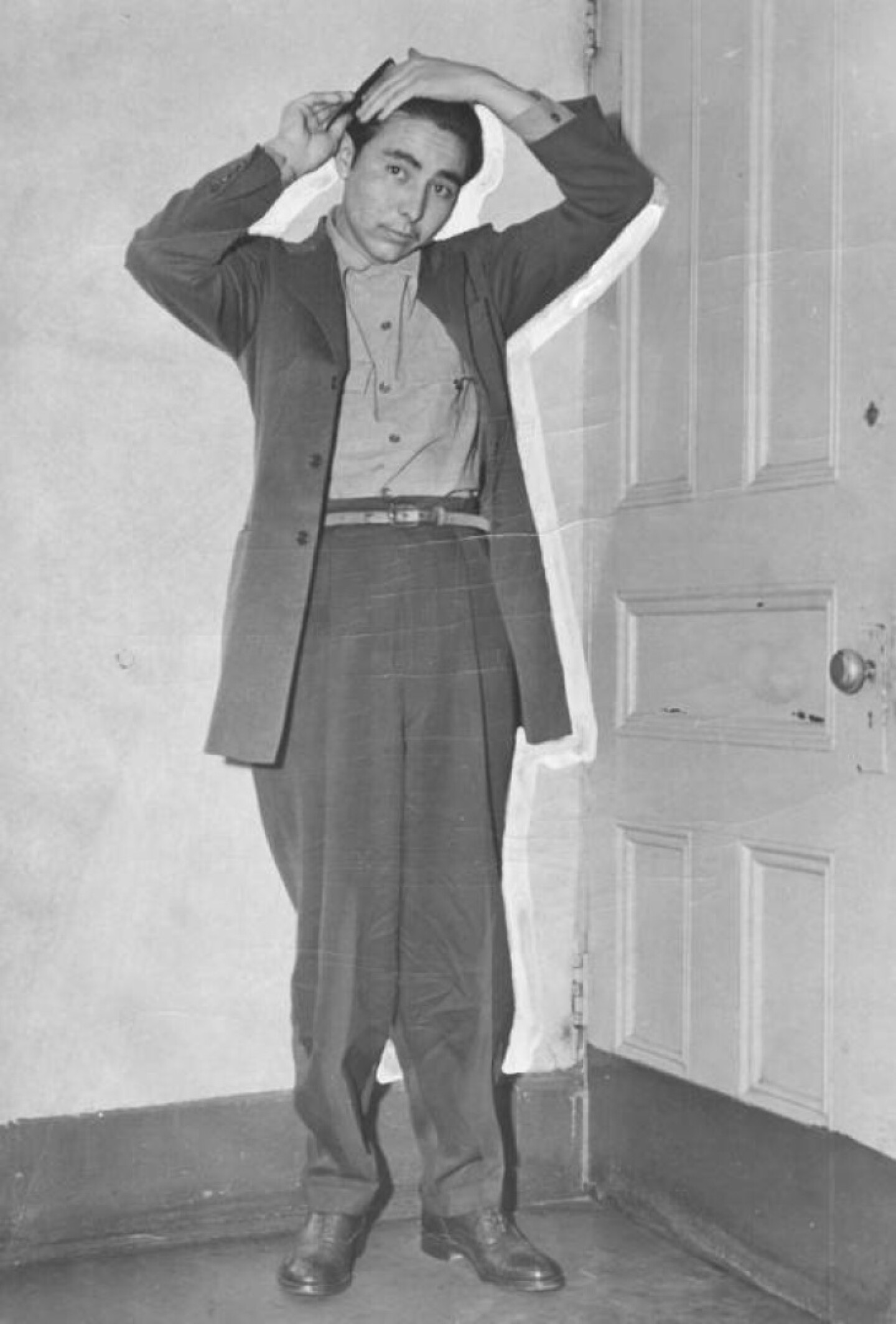

Style-conscious Harlem dancers began wearing loose-fitting clothes that accentuated their movements. Men donned baggy trousers with cuffs carefully tapered to prevent tripping; long jackets with heavily padded shoulders and wide lapels; long, glittering watch chains and hats ranging from porkpies and fedoras to broad-brimmed sombreros.

The image of these so-called “zoot suits” spread quickly and was popularized by performers such as Cab Calloway, who, in his Hepster’s Dictionary, called the zoot suit “the ultimate in clothes. The only totally and truly American civilian suit.”

Zoot Suits: ‘A Badge of Delinquency’

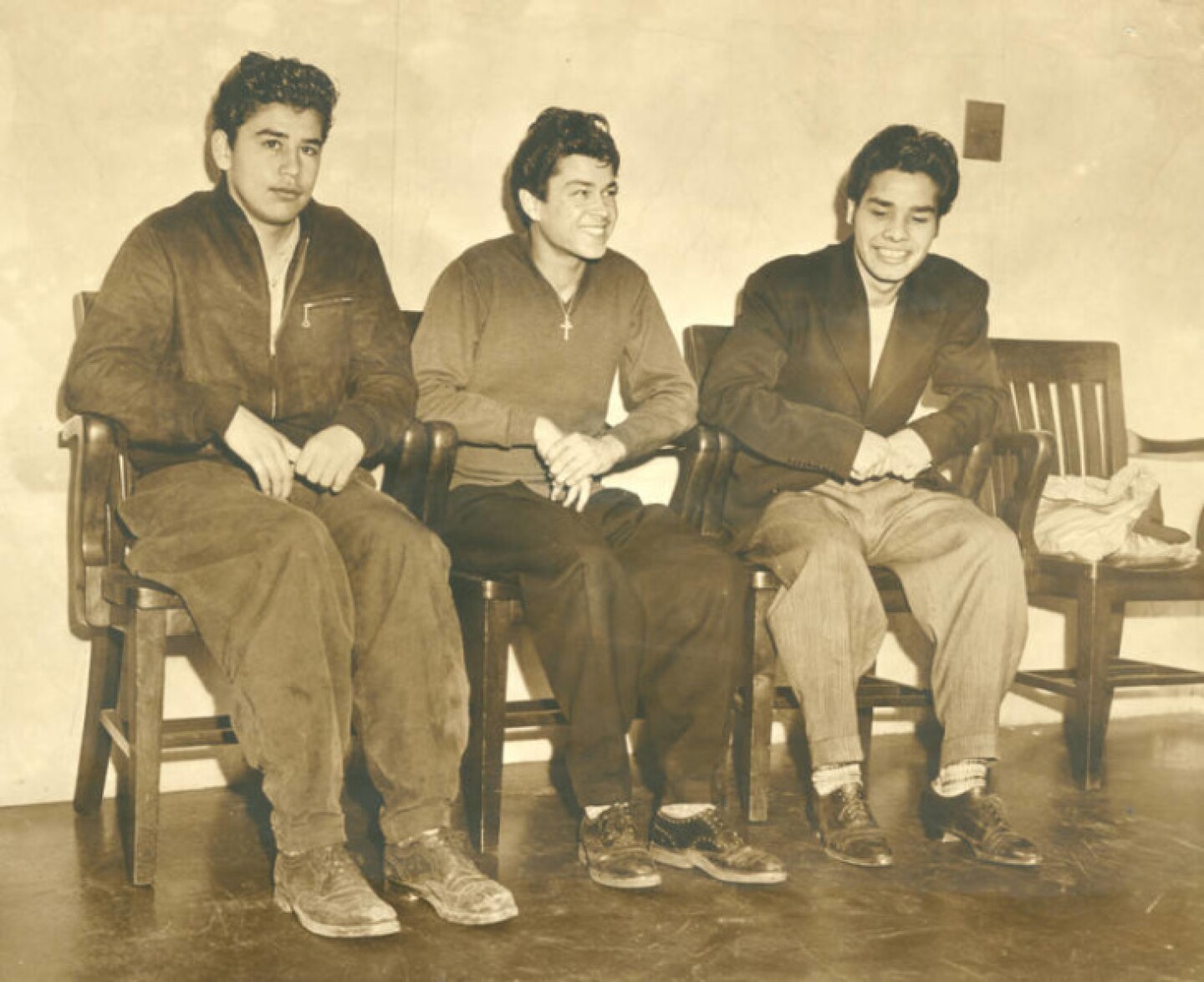

As the zoot suit became more popular among young men in African American, Mexican American and other minority communities, the clothes garnered a somewhat racist reputation. Latino youths in California known as “pachucos”—often wearing flashy zoot suits, porkpie hats and dangling watch chains—were increasingly viewed by affluent whites as menacing street thugs, gang members and rebellious juvenile delinquents.

Wartime patriotism didn’t help matters: After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War II, wool and other textiles were subject to strict rationing. The U.S. War Production Board regulated the production of civilian clothing containing silk, wool and other essential fabrics.

Despite these wartime restrictions, many bootleg tailors in Los Angeles, New York and elsewhere continued to make the popular zoot suits, which used profligate amounts of fabric. Servicemen and many other people, however, saw the oversized suits a flagrant and unpatriotic waste of resources.

The local media was only too happy to fan the flames of racism and moral outrage: On June 2, 1943, the Los Angeles Times reported: “Fresh in the memory of Los Angeles is last year’s surge of gang violence that made the ‘zoot suit’ a badge of delinquency. Public indignation seethed as warfare among organized bands of marauders, prowling the streets at night, brought a wave of assaults, [and] finally murders.”

The Zoot Suit Riots Begin

In the summer of 1943, tensions ran high between zoot-suiters and the large contingent of white sailors, soldiers and Marines stationed in and around Los Angeles. Mexican Americans were serving in the military in high numbers, but many servicemen viewed the zoot-suit wearers as World War II draft dodgers (though many were in fact too young to serve in the military).

On May 31, a clash between uniformed servicemen and Mexican American youths resulted in the beating of a U.S. sailor. Partly in retaliation, on the evening of June 3, about 50 sailors from the local U.S. Naval Reserve Armory marched through downtown Los Angeles carrying clubs and other crude weapons, attacking anyone seen wearing a zoot suit or other racially identified clothing.

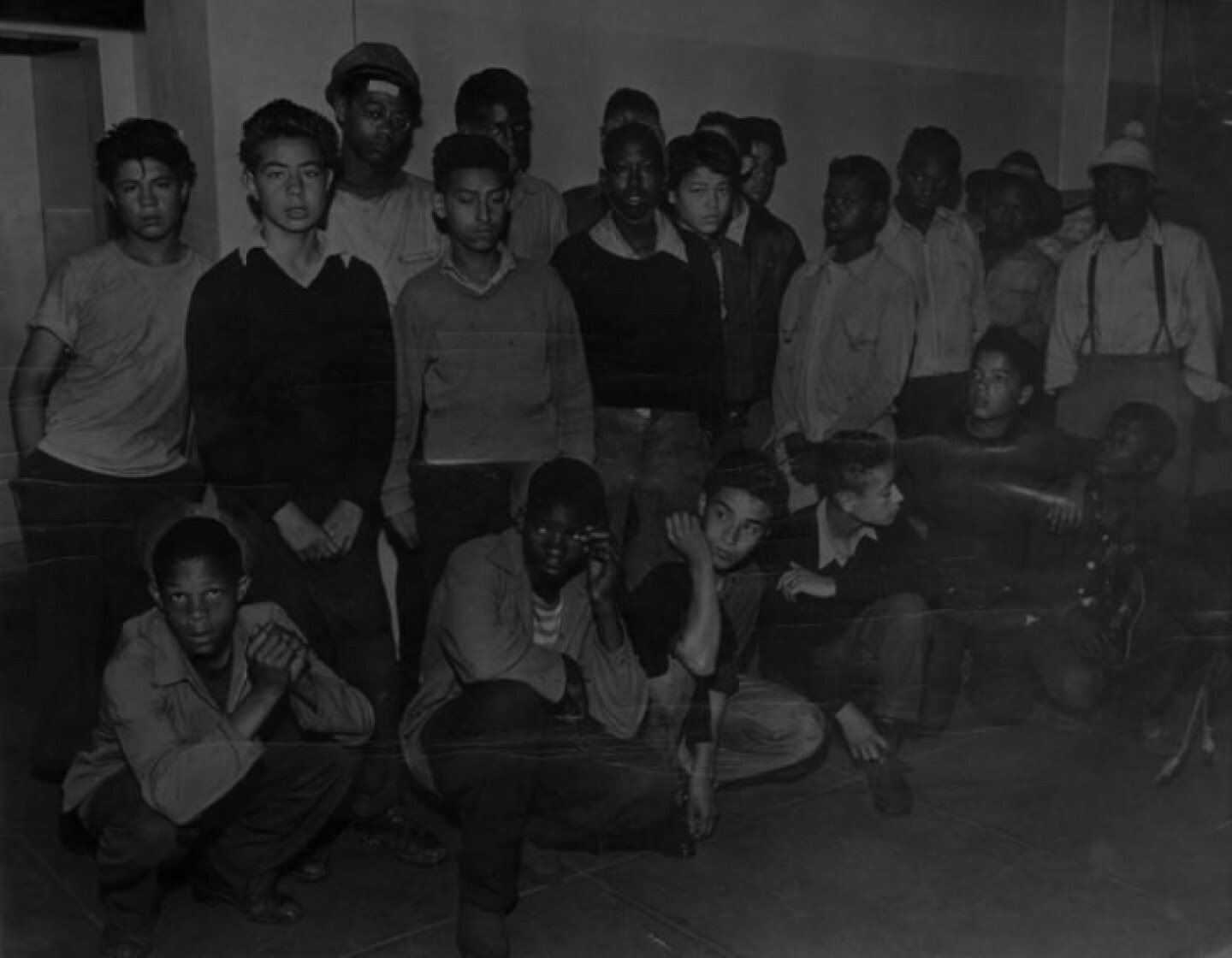

In the days that followed, the racially charged atmosphere in Los Angeles exploded in a number of full-scale riots. Mobs of U.S. servicemen took to the streets and began attacking Latinos and stripping them of their suits, leaving them bloodied and half-naked on the sidewalk. Local police officers often watched from the sidelines, then arrested the victims of the beatings.

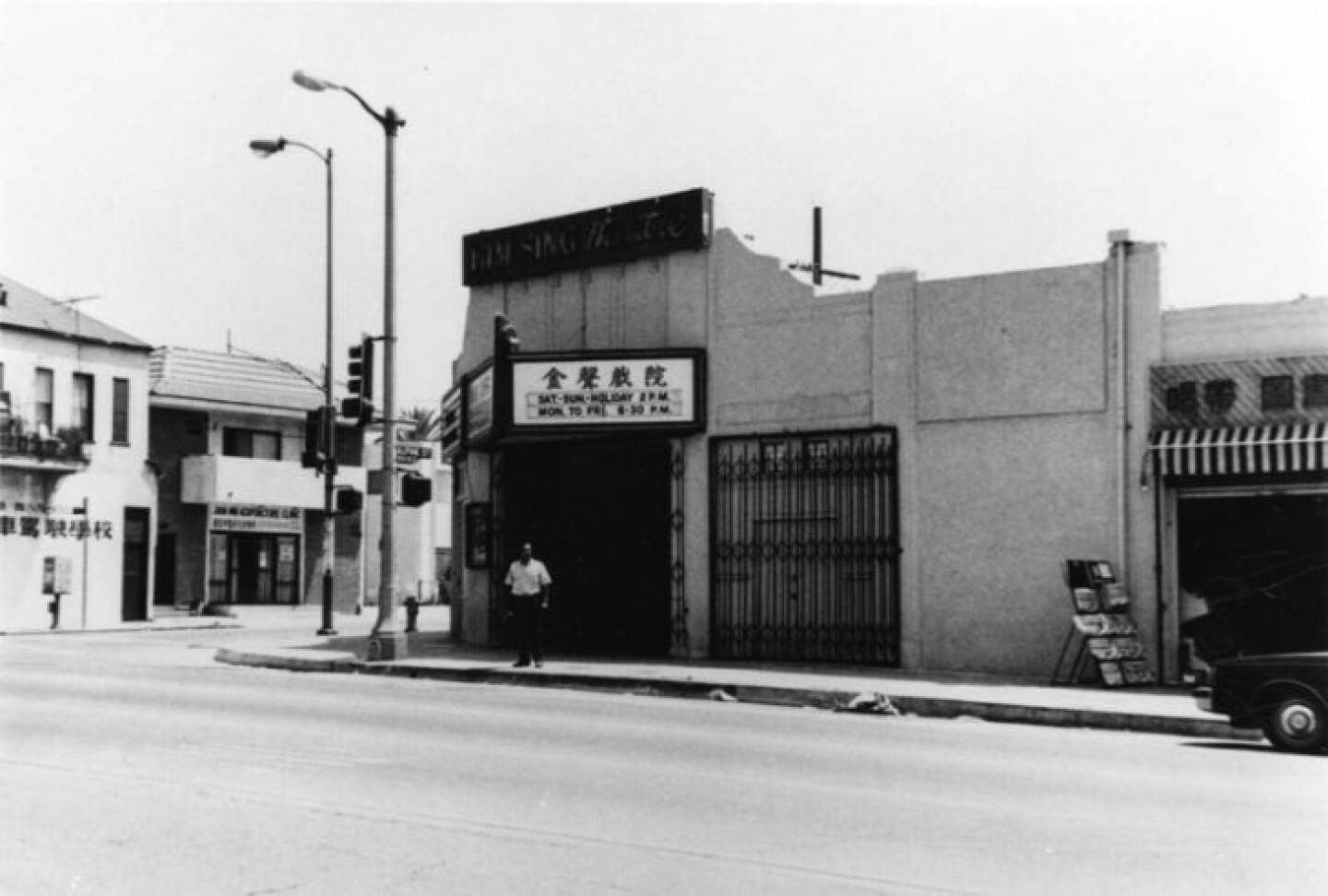

Thousands more servicemen, off-duty police officers and civilians joined the fray over the next several days, marching into cafes and movie theaters and beating anyone wearing zoot-suit clothing or hairstyles (duck-tail haircuts were a favorite target and were often cut off). Blacks and Filipinos—even those not clad in zoot suits—were also attacked.

The Zoot Suit Riots Spread

By June 7, the rioting had spread outside downtown Los Angeles to Watts, East Los Angeles and other neighborhoods. Taxi drivers offered free rides to servicemen to rioting areas, and thousands of military personnel and civilians from San Diego and other parts of Southern California converged on Los Angeles to join the mayhem.

Leaders of the Mexican American community implored state and local officials to intervene—The Council for Latin American Youth even sent a telegram to President Franklin D. Roosevelt—but their pleas met with little action. One eyewitness, writer Carey McWilliams, painted a terrifying picture:

“On Monday evening, June seventh, thousands of Angelenos … turned out for a mass lynching. Marching through the streets of downtown Los Angeles, a mob of several thousand soldiers, sailors, and civilians, proceeded to beat up every zoot-suiter they could find. Street cars were halted while Mexicans, and some Filipinos and Negroes, were jerked out of their seats, pushed into the streets, and beaten with sadistic frenzy.”

Some of the most disturbing violence was clearly racist in nature: According to several reports, a black defense plant worker—still wearing his defense-plant identification badge—was yanked off a streetcar, after which one of his eyes was gouged out with a knife.

Aftermath of the Zoot Suit Riots

Local papers framed the racial attacks as a vigilante response to an immigrant crime wave, and police generally restricted their arrests to the Latinos who fought back. The riots didn’t die down until June 8, when U.S. military personnel were finally barred from leaving their barracks.

The Los Angeles City Council issued a ban on zoot suits the following day. Amazingly, no one was killed during the weeklong riot, but it wasn’t the last outburst of zoot suit-related racial violence. Similar incidents took place that same year in cities such as Philadelphia, Chicago and Detroit.

A Citizens’ Committee appointed by California Governor Earl Warren to investigate the Zoot Suit Riots convened in the weeks after the riot. The committee’s report found that, “In undertaking to deal with the cause of these outbreaks, the existence of race prejudice cannot be ignored.”

Additionally, the committee described the problem of juvenile delinquency youth as “one of American youth, not confined to any racial group. The wearers of zoot suits are not necessarily persons of Mexican descent, criminals or juveniles. Many young people today wear zoot suits.”

Sources

A Brief History of the Zoot Suit: Smithsonian.com.

Zoot Suit Riots: Pomona College Research Library [online].

Remembering the Zoot Suit Riots: California Historical Society.

Los Angeles Group Insists Riots Halt: The New York Times.

Youth Gangs Leading Cause of Delinquencies: Los Angeles Times. Accessed via web.viu.ca.

The Los Angeles “Zoot Suit Riots” Revisited: Mexican and Latin American Perspectives. Richard Griswold del Castillo, San Diego State University.

Zoot Suits: A Fashion Movement that Sparked Mexican American Resistance

09 June 2017 | ANGELA O’SHAUGHNESSY | Yes! (original link)

Dressed in a white shirt and pegtop trousers, the fashion of the time for young males influenced by jazz culture, José Díaz headed to a friend’s birthday party in rural Los Angeles. It was the summer of 1942, and 22-year-old Diaz, who was born in Mexico but raised in the United States, was scheduled to report for induction into the U.S. Army the next day.

According to accounts, Díaz was excited about the U.S. entering World War II and looked forward to the opportunity to serve his country. Because he would be leaving home for boot camp, he decided at the last minute to attend the party, although he’d initially told his mother he didn’t feel up to going. Toward the end of the night, a group of young people known for trouble showed up seeking revenge for an earlier altercation. A fight broke out, and many were injured. Díaz was left beaten and stabbed, and would later die in the hospital from a brain contusion.

Much like today, fear of the other had firmly permeated the American psyche.

The incident, which became known as The Sleepy Lagoon Murder, sparked widespread fears among white Angelenos over “dangerous, unruly,” Mexican teens, mostly known as zoot suiters for their attire—ballooned pants and long coats. Then-Governor Cuthbert L. Olson used Díaz’s death as a call to action. The Los Angeles police arrested more than 600 Mexican American youth. More than 20 indictments were issued in Díaz’s death, and, in 1943, members of a group called the 38th Street Boys were convicted. One was sentenced to life in prison.

Within months, what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots would erupt.

In the throes of WWII, extreme patriotism reigned. Much like today, fear of the other had permeated the American psyche, and many working class whites were emboldened by a pervasive jingoism as the United States asserted its strength on the national stage, while disempowering its own citizens at home.

Japanese Americans were expelled into internment camps, Blacks migrated North in droves to escape racial hostility in the South, and The Bracero Program, the largest U.S. contract labor program, brought several thousand Mexican guest workers into Los Angeles. The “City of Angels” had a booming economy, but discriminatory policies in employment and housing kept people of color on the periphery.

Though about 350,000 Mexican Americans fought in WWII, (More than 500,000 Latinos—including 350,000 Mexican Americans and 53,000 Puerto Ricans served.), their very presence in urban areas was considered a threat.

It was Mexican youth who adopted the attire as an unofficial uniform of resistance.

Riots erupted in various cities across the nation, and the racial tension brewing in Los Angeles placed the Mexican American struggle front and center.

For first- and second-generation Mexican Angelenos, a sense of identity was necessary for survival. As they struggled to navigate older familial and generational values and widespread bigotry, fashion became an important form of cultural expression. For Mexican youth, who would call themselves Pachucos and Pachucas, the zoot suit did just that.

The flamboyant garb, inspired by the drape suits initially popularized by African American jazz musicians such as Cab Calloway, made its first appearances throughout nightclubs in Harlem and New Orleans. The long jackets with exaggerated padded shoulders, high-waisted ballooned trousers, and pork pie hats defined the look and also made it easy to jump, jive, and swing to the fast-paced jazz rhythms.

Women wore their own versions too, subverting the status quo and testing established notions of womanhood and femininity. Working class whites, Blacks, and other youth of color, including future activists Malcolm X and Cesar Chavez, embraced the look in its early days. But Mexican youth adopted the attire as an unofficial uniform of resistance—much like young Black boys today who are profiled, criminalized, and murdered in their hoodies for embracing urban fashion and choosing not to conform.

In a national effort to preserve resources, the War Preparedness Board banned the production of wool, pleats, cuffs, and long jackets—key elements that helped define zoot-suiter style. The 1942 mandate had practical purposes, and to resist was dangerous. Bootleg tailors continued sales, and those who stood in defiance were branded unpatriotic when American patriotism was at an all-time high.

There was nothing explicitly Mexican about zoot suits, but boldly demanding to be seen was an affront to American identity.

But Pachucos and Pachucas were American, and in the innovative ways marginalized ethnic groups have always done, they explored ways to carve out an identity in a society that wanted them to disappear. In turn, Mexican youth—as well as Black and Filipino zoot suiters—were hunted, brutally beaten, and stripped of their suits. They then watched servicemen burn their clothes in the streets. Mobs of hundreds of white sailors and Marines poured into Mexican neighborhoods and local hangouts and brutalized them with impunity.

The same bigotry plagues the country today, evidenced by the Latinos, Muslims, Blacks, and Asians subjected to vicious hate crimes for the color of their skin or for wearing “ethnic” clothing. Young zoot suiters learned the very act of daring to assert themselves was, in the minds of many, un-American. Nothing about the zoot suits was explicitly Mexican, but boldly demanding to be seen was an affront to American identity.

As the riots made national news and anti-Mexican sentiment persisted, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt expressed concern in her column, My Day:

“The question goes deeper than just [zoot] suits. It is a racial protest. I have been worried for a long time about the Mexican racial situation. It is a problem with roots going a long way back, and we do not always face these problems as we should.”

The weeklong race riots ceased when servicemen were confined to their bases and more than 500 Mexican youth were arrested. Smaller clashes continued shortly thereafter, and the L.A. City Council made wearing a zoot suit on Los Angeles streets punishable by a 30-day jail sentence. The riots were arguably the first fashion movement to cause mass civil unrest in American history.

Still, the zoot suit had lasting influence and the riots were a pivotal moment in Mexican American history. Zoot suiters became leaders in the formation of the Chicano Movement during the Civil Rights Era; fought barriers to education, fair pay, and housing; coordinated walkouts and strikes; and formed countless organizations addressing everything from the plight of farmworkers to student activism on college campuses. What’s more, they exposed a struggle that was uniquely Mexican, and helped to affirm Chicanos as a legitimate political force.

Zoot suiters demanded to be seen, and their suits embodied more than style.

The zoot suit spirit inspires urban Mexican style into the 21st century. Today, as inner-city youth continue to endure systemic racism, poverty, incarceration, police brutality, and gang violence, they still use fashion to reclaim their identity.

The policing of Black and brown people who dare to challenge the status quo and embrace their own culture, often without a political agenda, continues to this day. Bans on Black hairstyles in the workplace, schools, and the military in recent years (twists were only approved in 2014, locs just this year), or attacks on hijab-wearing women, are modern examples of the ways in which cultural expression is continually silenced. But the pushback from white dominant culture has undeniably been the catalyst for politicizing cultural identity at various points throughout history.

After all, zoot suiters demanded to be seen, and their suits embodied more than style. They became a bold political statement in the face of bigotry, cultural oppression, and injustice.

Youth of color have always been at the forefront of history’s key social movements: subverting cultural norms and giving the middle finger to white supremacy, police brutality, and gendered and racial violence by using fashion and self-expression as a means of not only coping with oppression and subjugation, but also of claiming space rightfully owed and deserved.

AIRED FEBRUARY 10, 2002 PBS (original link)

Zoot Suit Riots

LOS ANGELES ERUPTS IN VIOLENCE

Film Description

In June 1943, Los Angeles erupted into the worse race riots in the city to date. For ten straight nights, American sailors armed with make-shift weapons cruised Mexican American neighborhoods in search of “zoot-suiters” — hip, young Mexican teens dressed in baggy pants and long-tailed coats. The military men dragged kids — some as young as twelve years old — out of movie theaters and diners, bars and cafes, tearing the clothes off the young men’s bodies and viciously beating them. Mexican youths aggressively struck back. The fighting intensified and on the worst night, taxi drivers offered free rides to the riot area. One LA paper even printed a guide on how to “de-zoot” a zoot-suiter. When the violence ended, scores of Mexicans and servicemen were in hospital beds.

Zoot Suit Riots is a powerful film that explores the complicated racial tensions and the changing social and political landscape that led up to the explosion on LA’s streets in the summer of 1943. To understand what happened during those terrifying June nights, the film describes changes in the city’s population — the influx of new immigrants, the booming war-time economy, the huge number of service men on their way to the Pacific theater and a new generation of Mexican Americans who were more conspicuous, more affluent and more self-confident than their parents had ever dared to be.

Decked out in wide brim hats, baggy pants, high boots and long-tailed coats, these “zoot-suiters” called each other “mad cats.” They were “Terrific as the Pacific” and “Frantic as the Atlantic.” Crossing cultural lines and pushing the boundaries of race and class, they were trying to define for themselves what it meant to be an American in 1942 Los Angeles. Even though there was no evidence to connect “zoot-suiters” to crime, the kids’ posturing and self-assurance made Anglos nervous. Many Mexican American parents even agreed that something was wrong with their young people.

At the heart of this story lies an unsolved murder. On August 1, 1942, a 22-year-old Mexican American man was stabbed to death at a party. To white Los Angelenos, the murder was just more proof that Mexican American crime was spiraling out of control. The police fanned out across LA, netting 600 young Mexican American suspects. Almost all those taken into custody were wearing the distinctive uniform of their generation: zoot-suits. The tragic murder and the injustice of the trial that followed, coupled with sensational news coverage of both, fanned the flames of the racial hostility that was already running rife in the city. Within months of the verdict, Los Angeles was in the grip of some of the worst violence in its history.

With stunning film noir style recreations of Los Angeles in the 1940s and with eloquent first-hand accounts from key participants — sailors and the white citizens who supported them, suit-zooters and their families — the program deftly conjures up the flamboyant world of a Mexican American subculture, the bigotry and hatred of much of the white establishment, and the dedication of a few liberals who pressed for justice in the face of overwhelming opposition.

In exploring the shocking outpouring of hatred and resentment in wartime Los Angeles, this film teaches us about race relations in the United States today.

Judith F. Baca’s Great Wall of Los Angeles Archive, Newly Acquired by the Lucas Museum

02 April 2021 | MAXIMILÍANO DURÓN | Art News (original link)

Earlier this week, the Lucas Museum of Narrative Art in Los Angeles announced that it has acquired the archive for The History of California, Judith F. Baca’s epic mural cycle. More commonly known as the Great Wall of Los Angeles, Baca’s mural offers a vision of history from the perspectives of historically marginalized groups, including Indigenous, Latinx, Black, and Asian communities, as well as queer people and women.

“This monumental work by an iconic artist contributes to shaping a more inclusive view of life in the United States and California,” Sandra Jackson-Dumont, the Lucas Museum’s director, said in a statement announcing the acquisition. “This incredible repository uniquely positions the Lucas Museum to illustrate the significance of public murals to storytelling.”

The Lucas Museum’s acquisition of the archive includes more than 350 objects related to the creation of the Great Wall, from concept drawings and mural studies to blueprints and site plans to notes and correspondence. Objects from the archive will could be included in the Lucas Museum’s permanent displays, when it opens in 2023. (Originally slated to open in 2022, the museum has delayed its inauguration after the pandemic forced it to push back its construction schedule.)

[The Lucas Museum wants to change how an art museum can be a part of society.]

Baca first developed the idea for the Great Wall in 1974, and the initial 1,000 feet was completed in 1976, with additions continuing through 1983. Its creation was administered through the muralism-focused arts nonprofit she cofounded, the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC). The process for creating the mural’s imagery was collaborative, with Baca working with scholars, historians, and community leaders to research the stories it would tell. Baca then worked with a team of artists and young people, many of whom had been considered at-risk, to produce the work in the Tujunga Wash.

For Baca, the Great Wall was a way to artistically imagine various moments in U.S. history that she found to be under-known and glaringly missing from history textbooks. This, she realized, could be a way for people from these marginalized groups to learn about their own histories, from their struggles to their triumphs. Her mural begins with images of prehistoric animals who roamed the land, moves on to California’s earliest people the Chumash, images colonization from the perspective of Indigenous people, and extends to the 1950s, with scenes depicting the Great Depression, the deportation of 500,000 Mexican Americans, the Zoot Suit Riots, Japanese internment, and protests against racially restrictive housing covenants also included.

[Read about how Judith F. Baca created the Great Wall.]

Currently 2,700 feet long, the Great Wall will soon get an update, thanks to a $5 million grant from the Mellon Foundation that will allow Baca and her team to extend the mural’s imagery from the 1960s to the present and make it a full mile long. “It’s going to put those historical moments in the context of the time we’re living in—an interpretation of history from 2020 and 2021,” Baca told ARTnews earlier this year.

Below, a look at some of the preparatory sketches for the Great Wall that are now part of the Lucas Museum’s collection.

Photo : Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. © 1980 Judith F. Baca/Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives (SPARCinLA.org)

Judith F. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles 1950: Farewell to Rosie the Riveter: Final Coloration, Punto Perspective, 1983.

The 1950s section of the Great Wall opens with this iconic image depicting the struggles women faced during the postwar era. In her monograph on Baca, art historian Anna Indych-López writes, “Rosie the Riveter, symbol of the women who left behind their traditional roles as housewives to perform industrial jobs during World War II, resists her return to the domestic sphere, a process made graphic by a television image of a woman with a vacuum cleaner who attempts to suck Rosie back into the simulacra home.”

Photo : Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. © 1980 Judith F. Baca/Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives (SPARCinLA.org)

Judith F. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles 1950: The Development of Suburbia, 1983.

Abutting the Rosie the Riveter scene is one that shows the development of L.A.’s suburbs, in particular those in the San Fernando Valley, “reflecting the contentious history of white flight,” according to Indych-López. SPARC’s website expands on this: “Behind the televised images of American womanhood, an all‑American family of 2.5 kids (.5 equaling ‘Howdy Doody’) moves into a new suburb of endless box houses in endless rows, representing White flight from the Central City. Meanwhile, minorities and poor immigrants move from rural communities into the city. Rows of orange trees have been uprooted as suburbs sprawl throughout the L.A. basin and valleys.”

Photo : Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. © 1980 Judith F. Baca/Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives (SPARCinLA.org)

Judith F. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles 1950: Chavez Ravine and the Division of the Barrios, 2017.

One of the main focuses of the Great Wall is the experience of Latinx and Chicanx people in Los Angeles. During the development of L.A.’s freeways systems and Dodger’s Stadium, a number of the freeway interchanges were sited in the city’s East Side, which has historically been the heart of the city’s Latinx population. As a result, neighborhoods were divided by the freeways, effectively displacing the communities that had long called the area home. Similarly, Dodger’s Stadium is located on the site of Chavez Ravine, once a thriving Latinx community, that was cleared—in some cases through police violence—to build the baseball stadium, depicted here as a UFO dropping down into the city.

Indych-López writes, “Baca cleverly animates the freeway which encircles and divide up a Chicana/o family while its pylons crush their houses, creating a visual metaphor for the ways in which the freeway represents a force of destruction.”

Photo : Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. © 1980 Judith F. Baca/Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives (SPARCinLA.org)

Judith F. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles 1950: Indian Assimilation, 1983.

Beginning in the 19th century, generations of Native Americans and Indigenous peoples in the United States (as well as ones in Canada) were forced to attend residential and boarding schools, where children were separated from their families and community elders. There, these children were instructed in Christianity and Western education models, forbidden to speak the mother languages or practice their tribal rituals, and were often subjected to physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. All of this was done as a way to assimilate Indigenous peoples to white U.S. culture. The devasting effects of these forced assimilation practices are still felt in Indigenous communities across the continent today.

Photo : Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. © 1980 Judith F. Baca/Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives (SPARCinLA.org)

Judith F. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles 1950: Asians Gain Citizenship and Property: First Korean to Be Granted American Citizenship, 1983.

The United States has a long history of anti-Asian racism, beginning with the 1875 Page Act, which barred Chinese women from immigrating to the United States. Later, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prohibited the immigration of all Chinese people to the United States. Waves of Chinese immigration had begun decades earlier with the California Gold Rush and lasted through the construction of the transcontinental railroads. The Chinese Exclusion Act wasn’t repealed until 1943, with new laws that set strict quotas for the number of immigrants allowed into the United States each year. During World War II, Japanese Americans across the Western states were interned in concentration camps, at the same time that the 442nd Infantry Regiment, consisting of Japanese Americans, became the most decorated military unit in U.S. history. These stories are all depicted at various points in the Great Wall, and Baca also included a scene depicting a Korean person being naturalized as an American citizen.

Photo : Lucas Museum of Narrative Art, Los Angeles. © 1980 Judith F. Baca/Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives (SPARCinLA.org)

Judith F. Baca, The Great Wall of Los Angeles 1950: The Birth of Rock and Roll, 1983.

One of the mural’s lighter moments comes in this scene, in which Elvis Presley jams on a guitar in a movie seen by a group of people in American muscle cars at a drive-in. Behind Elvis is a portrait of Chuck Berry, and to his left are saxophonist Charlie Parker and singer Big Mama Thornton, whom Baca includes as an acknowledgment of the ways in which Black culture indelibly influenced the development of rock ’n’ roll.

Photos: The Zoot Suit Riots Happened This Week, 76 Years Ago. Here’s A Look Back At The Fashion Statement That Sparked A Racist Mob

07 June 2019 | Jessica Flores | LA List (original link)

The zoot suit riots are considered to be “the first time in American history that fashion was believed to be the cause of widespread civil unrest,” writes historian Kathy Peiss in Zoot Suit: The Enigmatic Career of an Extreme Style.

But the word “riot” is actually misleading, said Shmuel Gonzales, a blogger and local historian. It was actually more of an assault by groups of white U.S. soldiers and sailors, who were awaiting deployment during World War II. On June 3, 1943, the men charged through the city to harm young Mexican American men for wearing baggy (but stylish) suits. African American and Filipino men on the streets were also attacked.

The violence was the result of widespread panic among white Angelenos, who felt that “ethnic minorities were taking their claim on the town, and encouraging mixed race dancing during the age of segregation,” Gonzales said. To summarize: white people rioted because of mixed. race. dancing.

Reports from the time explain that white residents saw men in zoot suits as “menacing street thugs, gang members and rebellious juvenile delinquents.” And the L.A. Times fanned the flames. On June 2, 1943, the Times reported: “Fresh in the memory of Los Angeles is last year’s surge of gang violence that made the ‘zoot suit’ a badge of delinquency. Public indignation seethed as warfare among organized bands of marauders, prowling the streets at night, brought a wave of assaults, [and] finally murders.”

The June attacks were carried out with clubs and other crude weapons. And the resulting wave of racism inspired other mobs of servicemen to take to the streets, often stripping Latino men of their clothes and beating them until they were bloody and unconsious. Local police officers watched the beatings, then arrested the victims.

More servicemen, off-duty police officers and civilians joined in the mob mentality over the next several days, marching into cafes and movie theaters, beating up anyone wearing zoot-suit clothing or hairstyles.

No one was killed during the riots but hundreds of people were injured…and the event sparked other zoot suit-related racial violence in other American cities like Philadelphia, Chicago and Detroit.

This week marks the 76th anniversary of L.A.’s “riot.” But to find the origins of zoot suit fashion, you have to go back to Harlem in the 1930s.Support for LAist comes fromBecome a sponsor

Zoot suits originated out of drape suits, which became popular in black communities 1930s New York. The style quickly spread throughout the U.S. and became fashionable among performers like Cab Calloway. In L.A., a pachuco or pachuca became a common phrase for Mexican American men and women who wore zoot suits.

Despite strict rationing of wool and other textiles during WWII, many bootleg tailors in Los Angeles (and New York) continued to make the suits with high-end fabrics.

Today, many Angelenos still embrace the style by wearing its trademark threads — baggy trousers and long jackets with padded shoulders — especially in majority Latino neighborhoods like Boyle Heights. “It’s still a style that resonates,” Gonzales said. “People identify with it.”

But zoot suits were about more than just fashion. The style was a political statement for some men in L.A. and became a symbol for the racial tension in the city.

In honor of that history, please join us for a visual tour of the aftermath of the zoot suit fashion and the riots that followed, courtesy of the L.A. Public Library’s (amazing) photo archive.Support for LAist comes fromBecome a sponsor

Note that the original captions come from the Herald Examiner and are heavily biased, telling a different story of the “riot” events. Shmuel Gonzales said that’s because the Herald Examiner was “notorious as one of biased newspapers, repeatedly skewing the news and causing hysteria about working-class people of color and their children.”

The only newspapers that decried the Zoot Riots at the time (during the age of Jim Crow) was the L.A. Reporter and Eastside Journal published by Al Waxman (the uncle of Congressman Henry Waxman).

![]()