Many have said they were shocked to see how quickly the concert deteriorated into complete pandemonium.

See also below: Astroworld had a plan for mass casualty events and Tragedy at Travis Scott’s Astroworld ‘preventable,’ expert says

07 November 2021 | JUAN LOZANO, RYAN PEARSON and SALLY HO | AP via ABC News

HOUSTON — Screaming. Suffocating. Panicked. Unconscious.

The concertgoers at a highly anticipated Houston music festival Friday night say they were shocked to witness how the event brewed into pandemonium that left at least eight people dead.

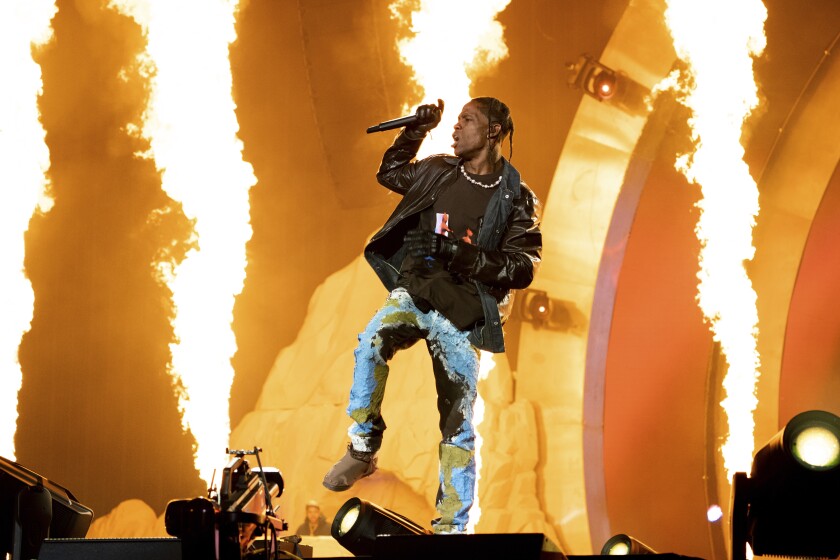

Rapper Travis Scott was the headliner for the sold-out Astroworld Festival in NRG Park, which was attended by an estimated 50,000 people.

Here, some of them describe the chaos they’re still trying to understand.

———

Ariel Little of New York was in the middle of the crowd in a prime viewing spot with her husband for only a brief minute before she started to struggle.

It was in trying to escape the increasingly packed venue that the couple realized how dangerous it was becoming.

Little’s voice quivered with emotion as she described how small she felt gasping for air as she was battered by the crowd.

“My chest is in so much pain from people pushing and crushing — literally crushing — my chest and in my lungs. And all I can remember is just screaming for him. ‘I gotta get out! I gotta get out!’ And people weren’t moving,” Little said. “They thought it was a joke but it was like literally people dying.”

Her husband, Shawn, surveyed the scene quickly to find a way out.

“There was a lot of people in my section that were kind of like screaming and having panic attacks just because it felt almost as if you were under an elevator and the elevator was coming down on you and there was nothing you could do about it,” Shawn Little said. “No one in my section at the time was moving because I think everyone was just in shock of how crazy and how panicked that everyone was. There was a lot of fear in people’s eyes.”

———

Madeline Eskins is an intensive care unit nurse who said she was one of the festivalgoers who passed out as the mass of people pressed closer to the stage. She was taken to a slightly less crowded area for medical attention, where she woke up.

Eskins, 23, of Houston, said she then saw someone nearby who needed medical help, and she told them she was a nurse. When a security guard overheard her, he asked if she could start helping others, Eskins said.

“There was three people on the ground getting CPR and the most disorganized chaos that I have ever seen in my life,” Eskins said.

Eskins said she tried to guide medical staff and volunteers on how to use a defibrillator, and she also helped to check for pulses and do CPR compressions on several people.

———

“When the main performer came out — like Travis — people got, like, compressed cause they just wanted to see him,” said Sal Salinas. “It was like you were suffocated in there. If you weren’t on the side or anything, you were getting suffocated.”

———

Niaara Goods, 28, of New York, said the crowd surged as a timer clicked down to the start of the performance.

“As soon as he jumped out on the stage, it was like an energy took over and everything went haywire. All of a sudden, your ribs are being crushed. You have someone’s arm in your neck. You’re trying to breathe but you can’t,” said Goods, who traveled to Texas to see friends and to celebrate a birthday.

She said she and her friends, one of whom was punched on the head and jaw, were quickly separated from each other but all escaped. Goods said she was so desperate to get out that she bit a man on the shoulder to get him to move.

“Some people are laughing at us — those who are screaming to get out. Because they thought it was funny. They didn’t realize it was terror,” she said.

Later, after getting to safety, she saw the injured streaming to safety in gurneys or in wheelchairs.

”It was literally the scariest night of my life. I literally thought I was going to die trying to get out. That’s just not what you pay for,” she said.

———

Gary Gaston, 52, of Houston said he went to the concert with his ex-wife, their 14-year-old son and the teen’s friend.

They felt so threatened after only a few of Scott’s songs that they decided to leave and meet outside by the medical tent.

When Gaston and his ex-wife arrived shortly after 10 p.m., he said they saw medical personnel start to bring at least eight people into the tent on gurneys, most of whom appeared unresponsive.

“It was surreal because you see these people being pulled out on these gurneys and people running into the medical tent, but the music is still going,” Gaston said. “People in the arena were unaware of it.”

———

Gavyn Flores said people kept trying to scoot into spaces where there was none to spare, while others tried to will their way toward the barricades to jump over to safety.

“They couldn’t get there because there were people like blocking them so those people like they had to just deal with it like because they couldn’t get out of the show,” Flores said. “They were like chanting ‘Stop the show!’ and there was a guy in the back getting CPR. So many people were getting CPR, like it was absurd.”

———

Julian Ponce said there were signs of injuries but he didn’t realize there were deaths until he got home.

“It was kind of mind-blowing, like we kept hearing people say, ‘Stop the show. Stop the show,’ but we didn’t know what was going on. We heard somebody was bleeding. We heard a lot of stuff and we weren’t too sure,” Ponce said. “I don’t even know how to feel. It’s just breathtaking.”

———

Associated Press reporter Acacia Coronado contributed from Austin, Texas.

Astroworld had a plan for mass casualty events. It’s unclear whether promoters followed it

07 November 2021 | Zach Despart, John Tedesco, Dug Begley, Staff writers | Houston Chronicle

Astroworld had a plan for all sorts of emergencies. It designated who could stop a performance and how. It included a script for how to announce an evacuation. It detailed how to handle a mass casualty event.

The Houston Chronicle obtained the 56-page “event operations plan,” which the festival promoter developed to ensure the safety of 50,000 guests at the sold-out event at NRG Park.

“Astroworld, as an organization, will be prepared to evaluate and respond appropriately to emergency situations, so as to prevent or minimize injury or illness to guests, event personnel and the general public,” the document states.

Attendees described an entirely different scene: an overwhelmed venue where security personnel were unable to prevent fans from being crushed. Where medics were too few. And where production staff were unwilling to halt the show despite pleas from fans that others had collapsed.

The tragedy at Astroworld Festival

Attendee Maximiano Alvarado said he witnessed a medic treat two victims by herself. He heard her say she could not detect a pulse on either.

“Finally paramedics come, and they started doing CPR,” Alvarado said. “I didn’t even pay attention to Travis more than half of the time because there were so many things, cops and stuff, going on around me.”

All of the nine concert promoters and security personnel named in the document as responsible for managing the show declined to comment on what went wrong or did not respond. They include Seyth Boardman, author of the plan and the festival’s safety director, and Brad Wavra, a vice president at promoter Live Nation.

Harris County Judge Lina Hidalgo said a review of the plan — and whether it was properly followed — should be part of an objective, third-party investigation of the tragedy.

“What I know so far is that Live Nation and Astroworld put together plans for this event,” Hidalgo said Saturday. “A security plan, a site plan. That they were at the table with the city of Houston and Harris County. And so perhaps the plans were inadequate. Perhaps the plans were good, but they weren’t followed. Perhaps it was something else entirely.”

The plan for the Astroworld Festival said that the executive producer and the festival director had the ultimate authority to stop the show. In a dire emergency, the document said an incident command post would be established and the incident commander could order the power to be diverted from the show if lives were in “immediate danger.”

That step was never taken.

Stopping a human crush once it has started is difficult, said a security guard who has worked NRG events in the past. Video from attendees in the minutes before Scott took the stage at 9 p.m. shows fans jumping barriers by the front of the stage to escape overcrowding, which could have been a critical, missed warning sign for security staff, he said.

“You have to pay attention to that stuff, when people are getting pushed against the fences,” said the guard, who asked to remain anonymous because he still works in the security field. “If you can’t put a stop to it then, it’s a lot harder to control.”

Houston police officials said they asked concert promoters to halt Scott’s concert after the crowd rushed the stage and fans began collapsing around 9:30 p.m. Houston Fire Chief Sam Peña said a “mass casualty” event was declared at 9:38 p.m.

“Suddenly we had several people down on the ground, experiencing some type of cardiac arrest or some type of medical episode,” said Larry Satterwhite, executive assistant chief at the Houston Police Department. “And so we immediately started doing CPR and moving people right then. That’s when I went and met with the promoters and Live Nation, and they agreed to end early in the interest of public safety.”

It’s unclear whom Satterwhite spoke with or how long that conversation lasted. Police Chief Troy Finner later said there were concerns about shutting down the show too abruptly and risking a riot.

But concert attendees said Scott didn’t end the show early — he continued playing his full set of songs for 37 minutes after the mass casualty event was declared by the fire department. The show finally ended at 10:15 p.m., they said. Finner and Mayor Sylvester Turner said it ended five minutes earlier at 10:10 p.m.

The police department said it would not grant any interviews on Sunday. Peña said that even though the plan didn’t call for it, the fire department positioned extra EMS units nearby and they swiftly responded.

“We went ahead and pre-planned in anticipation for a contingency,” Peña said. “That’s the reason why we had units deployed around the perimeter and were able to respond so quickly.”

Still, even that measure was inadequate. The fire department dispatched an additional 28 units to the scene after declaring the mass casualty event, according to radio traffic.

The emergency plan stated that if someone is seriously injured, concert personnel can request a partial evacuation of the area. The plan also offered scripts on what to say to concert attendees in the event of an evacuation.

It’s unknown if any requests for partial evacuations were sent to the event’s supervisors. Live Nation did not use the PA system or video boards to broadcast any safety messages Friday evening, attendees said.

The report recommended dealing with civil disturbances or riots by maintaining control from the outset of the show.

“The key in properly dealing with this type of scenario is proper management of the crowd from the minute the doors open,” the report stated. “Crowd management techniques will be employed to identify potentially dangerous crowd behavior in its early stages in an effort to prevent a civil disturbance/riot.”

But crowd-control efforts fell short earlier in the day, when a VIP entrance was breached by hundreds of fans at 2 p.m. The plan made no mention of a similar breach in 2019, nor how security measures had been improved in response to it.

The plan also details how to handle a fatality, including how to report it up the chain of command.

“Notify Event Control of a suspected deceased victim utilizing the code ‘Smurf,’” the plan stated. “Never use the term ‘dead’ or ‘deceased’ over the radio.”

Alejandro Serrano contributed reporting.

(Jamaal Ellis / Associated Press)

Concert safety expert: Deaths at Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival were ‘preventable’

Randall Roberts7-9 minutes 07/11/2021

When concert safety consultant Paul Wertheimer first saw video from Travis Scott’s Astroworld Festival in Houston, where at least eight people died Friday during a crowd surge in Scott’s set, his conclusion was based on decades of experience.

“This was preventable. The crowd was allowed to get too dense and was not managed properly,” he said. “The fans were the victims of an environment in which they could not control.”

Wertheimer has been leading the charge for concert safety since 1979, when he was an on-site investigator the night 11 people were trampled to death at a Cincinnati concert by the Who. He compiled the post-concert report on the failings, including festival seating, that led to the deaths, and across the next four decades has advocated for crowd safety measures through his company Crowd Management Strategies.

In 2000 at the Roskilde Festival in Denmark, when nine people were trampled to death at a Pearl Jam concert, Wertheimer consulted with the Danish government on preventive solutions. He’s testified in civil suits against concert promoters and security companies. As the decades have passed, Wertheimer has come to an unfortunate conclusion.

“Life is cheap. Young people are still exposed to the extreme dangers,” he said. The main reason being that “the people who organize and approve these events are not held criminally liable for gross negligence. And as long as promoters, artists, security, venue, operators and city officials who approved these plans are not held criminally liable — this is going to drone on.”

The Who, Pearl Jam and Travis Scott tragedies all share a similar trait: so-called festival seating. A first-come, first-serve approach to ticketing, it replaces reserved seats, or any seats at all, in favor of a shoulder-to-shoulder, general admission experience. Those who have been to a festival in the last three decades, be it Coachella, Stagecoach, Bonnaroo or Woodstock ’99, have partaken in festival seating. Legendary ’60s concerts Woodstock and Altamont utilized festival seating, but even in the early 1970s its use was rare enough as to warrant a mention in reviews.

Festival seating offers fans willing to line up early the opportunity for closer views, and the space in which to dance or, at a Travis Scott concert, to mosh. For promoters such as Astroworld’s Live Nation, festival seating means more tickets sold. Wertheimer said that a seat might take up 6 square feet of space; a packed event such as Astroworld might only allow for 2 square feet of room per person.

Crowd-control measures have improved since 1979. Goldenvoice’s Coachella, held at the Empire Polo Club in Indio, separates its main stage pitch into grids divided by heavy iron barriers, and the resulting canals prevent large-scale mosh pits or heaving crowds from getting out of control. The approach also allows for security to access trouble spots more easily.

Wertheimer said that barriers, which he describes as “like a reef that you put in the ocean to break up the waves,” can be effective, but not always. The Roskilde Festival used barriers to break up the crowd, he explains. “If you overcrowd a place, people can get crushed in between. It’s not necessarily going to work if you’re not taking other precautions.”

He added: “Travis Scott was known to have chaotic concerts, so it likely wouldn’t work with him. If it’s Pink Floyd, it’s going to work.”

Most often, the promoter is responsible for following crowd safety guidelines, Wertheimer said, noting that at particularly high-energy shows such as Scott’s, security guards usually maintain some sort of presence, not just on the perimeters but in the crowd itself. But Wertheimer said that some major security firms instruct their personnel to avoid dangerous situations. “Their manuals say ‘Don’t get involved. You could get injured and then we’ve got workman’s comp. Or contact your supervisor.’ So people are dying and you’re trying to reach your supervisor.”

One Astroworld attendee specifically noted the lack of security personnel. “I’ve been to Lollapalooza in Chicago, it was nothing like that. There should be a lot of security there, just to be safe,” Julian Ponce, 21, told The Times. A video from earlier in the day documented a rush of fans breaking through the VIP gates, only to be thwarted by officers on horseback.

Houston Police Chief Troy Finner acknowledged the earlier breach during a Saturday news conference: “It was something we got under control,” he said.

“There are a lot of questions that still need to be answered,” Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner said, stating that 528 police officers were assigned to the concert, “plus 755 security guards provided by Live Nation.”

Lina Hidalgo, chief executive for Harris County surrounding Houston, noted that the festival stepped up its security over the last Astroworld event by more than 150 personnel, after a barricade breach in 2019.

“It doesn’t matter how many police officers and security were there if they’re not in the proper location and they’re not trained in crowd management,” Wertheimer said of those numbers. “None of those people were in the crowd. Not enough of them were near the front barriers.” He added that most often, police officers aren’t assigned to crowd management anyway.

Concert promoter Live Nation issued a statement that read: “Heartbroken for those lost and impacted at Astroworld last night. We will continue working to provide as much information and assistance as possible to the local authorities as they investigate the situation.”

Houston Fire Chief Samuel Peña said the concert was inspected in advance, including access to entrances and exits. “What we’re looking into is what led to the crowd surge,” Peña said. “It was the crowd control at the stage that was the issue.”

Wertheimer said he takes specific issue with something that Peña said during the news conference on Saturday morning, that “the crowd began to compress towards the front of the stage, and that caused some panic, and it started causing some injuries.”

That’s framed entirely wrong, Wertheimer said. “When the fire chief of Houston says people were panicking, it tells me right off the bat he’s never been in a crowd crush. People were not panicking. They were trying to save their lives and save the lives of people around them.”

“There was like no airflow in there. It was just like primal instinct: I had to get out,” Astroworld attendee Gerardo Abad Garcia, 25, told The Times.

Whoever is to blame, lawsuits will probably follow. In the wake of the deadly Who concert, victims’ families sued not only the band, but the venue, its directors, the city of Cincinnati and the concert promotion company.

“Sixteen-year-old Suzy, or 18-year-old Johnny, are not crowd managers, fire marshals or security guards,” Wertheimer concluded. “They have a right to assume somebody is looking after their safety, but as is the case at concerts and festivals, all too often there is no safety net for them — and they’re the last ones to find that out.”

![]()